As people who live in rural areas, we are used to the potholes that jar our vehicles and rattle our teeth. Likewise, the financial statements that measure the position and performance of our farm businesses have potholes that are sometimes difficult to navigate, too.

The Balance Sheet is one of the four recommended financial statements by the Farm Financial Standards Council (FFSC)[1]. A balance sheet has three major sections: assets, liabilities, and owner equity. While there is more to it, owner equity is generally a residual after subtracting liabilities from assets. Liabilities are fairly straightforward: How much do you owe others? That leaves the last section, assets, fraught with pits and potholes on how to determine a reasonable, accurate, and consistent value!

Cash is easy: $100 of cash is a $100 asset value. However, what is the reasonable, accurate, and consistent value for the 10,000 bushels of stored grain, the bunker full of corn silage, the feeder cattle, the raised breeding livestock, a tractor, the land, or an open-hedge position?

Complicating matters is that there are two recommended balance sheets: Cost Basis and Market Basis. You might think that cost would be used for cost-basis sheets and market value would be used for market-basis sheets. Oh, if it was only that easy! The challenge in reasonably, accurately, and consistently valuing assets is that cost is not always used for cost-basis balance sheets and market value is not always used for market-basis balance sheets.

Value Inventory and Other Assets

Think about the variety of ways that you could have an inventory asset of corn.

- Corn growing in the field, not yet harvested

- Raised and harvested corn in storage intended for sale

- Raised and harvested corn in storage intended for feed use

- Purchased corn for later resale (not common)

- Purchased corn for use as feed

- Purchased and raised corn that have been co-mingled

- Raised corn that you have forward contracted, hedged, or have secured by a PUT option

Each of these types of corn inventory can be valued differently for a balance sheet.

The FFSC provides guidelines for how to value inventory and other assets. The FFSC follows Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) until the unique characteristics of production agriculture suggests an exception. (Raised crops and livestock intended for sale is one of those exceptions.) GAAP requires that inventories be valued at cost. However, for inventories of harvested crops and livestock held for sale, the FFSC Guidelines state: “agricultural producers may value those inventories at the current estimated selling prices less cost of disposal when all of the following conditions exist: Reliable, readily determinable, and realizable market price; Relatively insignificant and predictable costs of disposal; and Available for immediate delivery” (FFSC Guidelines, page 38).[2]

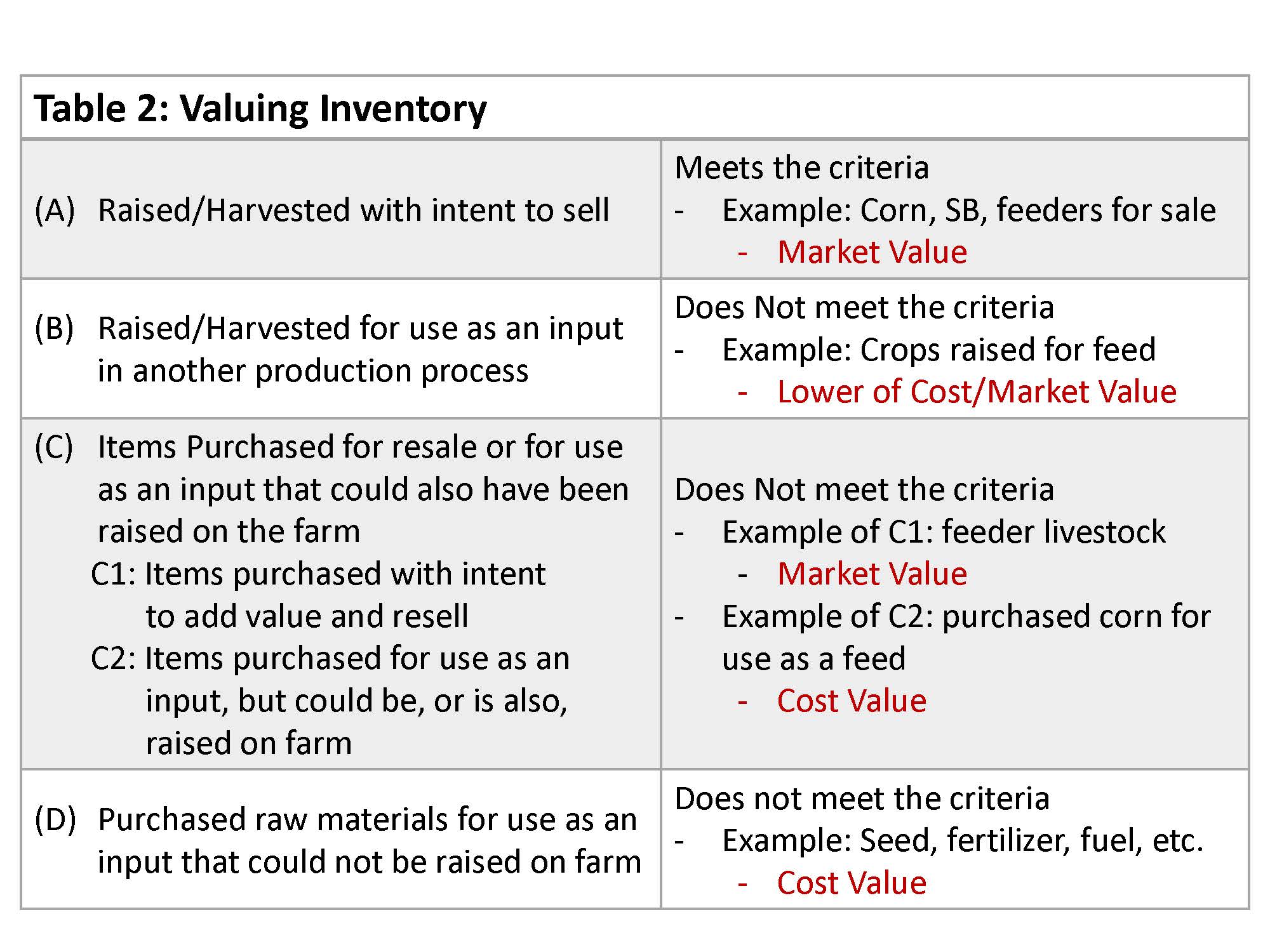

The FFSC separates inventory into four categories, A–D (left column of Table 2).

Category “A” are those crops and livestock that were raised on-farm with the intent to sell. This category meets the criteria listed above and therefore the recommendation is to use current market price (less any cost of selling) as the value of the asset.

Category “B” are also products that were raised on-farm, but the intent is not to sell them, but rather use them as an input in another production process. Crops raised for feed is a common example. Generally, these products do not meet the criteria and the FFSC recommends the lower of cost or market value. That can be a dilemma because there is no purchase cost, only the cost it took to raise the product, which may not be easily determined.

Category “C” are purchased inventory, but a specific kind of purchased inventory, which is that it could also have been raised. Purchased feeder cattle and purchased corn (for feed) are two examples of purchased products that could have been grown on-farm. Category “C” includes two subcategories. The first (C1) is products purchased with the intent to add value and resell (feeder cattle). The nature of this type of inventory is that it changes in value as more pounds are put on and the balance sheet should recognize the increased value versus its original cost. The second (C2) is products like corn purchased with the intent to use as an input (feed). The FFSC recommendation is the lower of cost or market value. Table 2 reflects my personal preference, which is to value at cost.[3]

Category “D” are purchased raw materials for use as an input and is inventory that could not be grown, such as seed, fertilizer, and fuel. There is a definable purchase price and the FFSC recommends using cost value on the balance sheet.

Recommendations

These recommendations are rife with “But, what if…” questions. For example, “But, what if the corn I purchase with an intent to use as feed is co-mingled with corn I raised?” In the case of co-mingled products, the FFSC recommends assuming that all raised product is used first and what is left is purchased product. If more inventory is available than the amount of purchased product, then use a prorated value.

However, let’s refrain from chasing the squirrels of the “But, what if…” questions and instead recall three important words: reasonable, accurate, and consistent. The last of these words, “consistent,” may be the most important. Over time, you want your balance sheet to show “real” changes in financial position. If you are consistent in how inventory and other assets are valued, then the “change” in owner equity is more likely to be “real” versus just a reflection of changing valuation methods.

What does this mean for you tomorrow after breakfast? Talk to your records/bookkeeper and find out how different kinds of inventory are valued. Are different kinds of inventory categorized and valued differently? If so, what is the categorization and how is it valued? Is it done the same way every year? What are the standard operating procedures for determining quantities of inventory and appropriate prices? Are those procedures in writing? If changes are warranted, then you may want to change the past couple of balance sheets as well so that your trends are comparable. Finally, be sure to provide footnote explanations of any changes in procedure written for all to see.

An accurate balance sheet can be used together with other financial statements to determine where the balls and chains holding back profitability might be. However, valuing assets is fraught with potential pits and potholes. One can fix those pits and potholes through establishing accounting procedures and practices that are reasonable, accurate, and most importantly consistent.

If this article was helpful, check out more Extension Farm Pulse Articles and Programs

[1] The FFSC is an organization that provides standards for the creation and analysis of farm financial statements (https://ffsc.org/).

[2] Financial Guidelines for Agriculture: Recommendations by the Farm Financial Standards Council. January 2021. (https://ffsc.org/).

[3] The FFSC Guidelines make the argument that the product could be resold. If it is resold, then its intent and character look more like category A, which is valued at market. This is a challenging explanation and, for simplicity, my preference is to consistently value C2 inventory at cost.