In farming, sweat equity is a term that is loosely used to define the practice of using a commodity or capital asset to replace some of the cash wages for employees. Sweat equity is a means for aspiring farmers to gain assets that will lay the foundation of their business. Often times farms do not know how to document sweat equity as a payment for wages. This fact sheet addresses how to correctly document sweat equity arrangements.

Reporting Non-Cash Wages

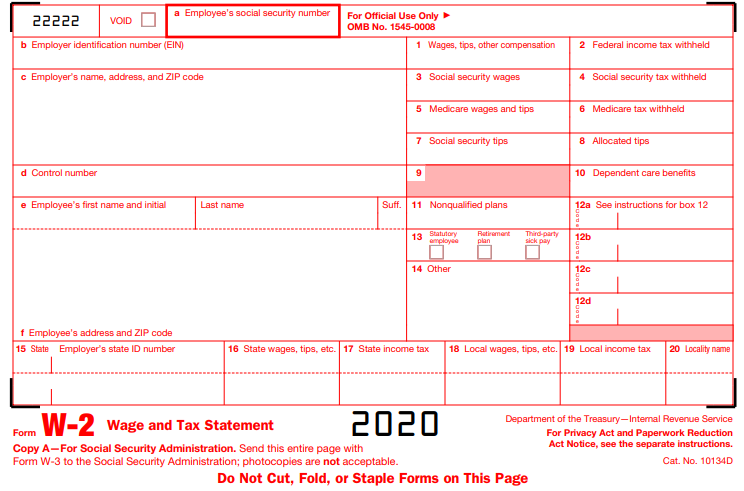

Wages paid to an employee in the form of a commodity (grain, milk, livestock, etc.) are considered taxable income under I.R.C. § 3121(a)(8)(A). Therefore, they must be reported on the employee’s W-2 form [Figure 1) in Box 1 (wages, tips and other compensation). However, they are not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes (FICA taxes) for either the employer or the employee. In addition, they do not have to be reported in Box 3 or 5 (social security, Medicare wages, and tips).

The employee has a basis in the commodity equal to the value noted on the W-2 in box 1. Basis is the difference between the local cash price of a commodity and the price of a specific futures contract of the same commodity at any given point in time. A subsequent sale of the commodity by the employee will trigger a taxable gain or loss depending on whether the sale price exceeds or is less than the basis of the commodity. If the employee is not a dealer in the commodity and does not sell the commodity in the course of the farm business, the sale should be reported on Schedule D (Form 1040). If the employee is a dealer or farmer, the sale should be reported on Schedule C (Form 1040) or Schedule F (Form 1040), respectively.

The employer can claim a deduction for the value of the commodity paid to the employee but should report income as if the commodity had been sold for its fair market value.

IRS Guidelines

In 1994 the IRS issued guidelines for dealing with non-cash payments in exchange for farm labor. These guidelines are not binding on any party because the facts and circumstances of each case determine whether a payment constitutes “wages” for employment tax purposes. While the guidelines acknowledge that non-cash wages are not subject to FICA taxes, they provide a fairly narrow interpretation of Internal Revenue Code § 3121(a)(8)(A). Taxpayers can choose not to follow these guidelines, but they are more likely to be challenged in an audit by the IRS when they do not.

While there are many factors that can be used to determine if a transfer of in-kind compensation has occurred, these factors can be divided into two components: 1) Dominion and Control and 2) Cash Equivalency.

Dominion and Control

The first component determines if the employee exercises dominion and control over the commodity. The six factors IRS examiners consider when determining if the employee exercises dominion and control are:

- Documentation: Documentation helps IRS examiners understand the transaction and offers evidence of the parties’ intent upon entering into the transaction. Documentation of both the employment relationship, including compensation practices, and the transfer of commodities is extremely important evidence in establishing a bona fide transfer of non-cash payments.

-

- Employment Relationship: The employment relationship is outlined in the wage payment agreement. However, the wage payment agreement can be amended to include non-cash payment transactions. Non-cash payment transactions should be described in a written contract, employment agreement, or other written evidence, such as meeting minutes or posted employee announcements.

- Employment Relationship: The employment relationship is outlined in the wage payment agreement. However, the wage payment agreement can be amended to include non-cash payment transactions. Non-cash payment transactions should be described in a written contract, employment agreement, or other written evidence, such as meeting minutes or posted employee announcements.

-

- Transfer of Commodities: The transfer of commodities for non-cash payments should be documented by receipts, contracts, bills of sale, or other documents that record the transfer of assets. Weigh tickets, veterinary inspection tickets, breeding certificates, formal registration records, and receipts showing the employee has incurred storage and feed costs are examples of other documentation that record the transfer of assets.

- Marketing of the Commodity: After the commodity is transferred to an employee, the employer cannot help the employee in the marketing of the transferred commodity. For example, if the employee sells the transferred commodity the employer cannot specify the selling price. If the employer specifies the selling price the employee has failed to exercise dominion and control over the commodity. However, the employee can contract with the employer to sell the commodity on his/her behalf. The guidelines recognize that, in some cases, the employee must associate his/her commodities with the employer’s commodities because of the demands of the purchasers. For example, the market may require such association if the employee’s quantity is small. The employee must be able to demonstrate that there are significant reasons to act in concert with the employer in marketing products.

- Risk of Gain or Loss: A transaction will likely be treated as a non-cash payment of wages if the employee assumes a greater amount of risk. When compensation is stated as a percentage of production, the employee is assuming the most risk. There is less risk when the compensation is stated as a fixed quantity of a commodity. If the compensation is stated as a fixed dollar value of the commodity, the payment will be treated as a cash payment. This payment will not qualify for the FICA exemption and needs to be added to lines 3 and 5 of the W-2. [Figure 1]

- Employee’s Holding Period: The employee’s holding period is the length of time an agricultural commodity is held by the employee. If the employer sets up a sales transaction with a third party prior to giving the commodity to the employee, the resulting income received by the employee for this transaction will be treated as a cash payment. This payment will not qualify for the FICA exemption and needs to be added to lines 3 and 5 of the W-2 [Figure 1]. The employee has to show management of the commodity and time is needed to do this. The commodity cannot move from the employer to the employee and immediately to the buyer. When this happens it is the same as the employer giving the employee the money from the sale. The employee needs to have some investment in the commodity for it to count as a commodity payment.

- Cost of Ownership: Once the commodity has been transferred the employee should be responsible for the costs necessary to maintain it. If the employee uses the employer’s facilities to maintain the commodity, the employee should pay rent on those facilities.

- Identification of Non-cash Payment: A bona fide non-cash payment should involve the transfer of a specific, identified commodity or other product. Hogs, cattle, and other livestock should be tagged, marked, branded, or segregated into separate pens at the time the commodity is transferred to the employee. The documents evidencing the transfer of fungible farm products should identify the nature, grade, and quality of the commodities used to pay in-kind wages. Fungible farm products are items that are interchangeable because they are identical to each other for practical purposes. No. 2 yellow corn, is a fungible good because it does not matter where the corn grew; it is essentially the same product. All corn designated as No. 2 yellow corn is worth the same amount.

Cash Equivalency

The second component focuses on whether the in-kind payment is equivalent to cash. Several of the factors considered in this component have already been discussed in relation to the first component. These include specifying a dollar quantity of commodities, the length of time the commodity is held by the employee, and the negotiability of the document used to transfer the commodity. In addition to those factors, the following factors are addressed:

- Cash Advances: Cash advances made to employees by an employer that are to be satisfied upon sale of the commodity are treated as cash wages.

- Immediate Conversion: If the employer knows that the employee will immediately convert the in-kind payment to cash, the payment will be treated as a cash wages.

- Sole Source of Income: When the in-kind payment is an employee’s only source of income for his/her agricultural labor, the transaction will be questioned. The transition will be questioned because the employee will need to convert the payment to cash to pay for living expenses. To determine if this source of income is FICA tax exempt, the IRS will look at the employee holding period, or how long they held onto the commodity before converting it to cash.

Other Factors

IRS guidelines note other factors that are important in determining if a non-cash wage is FICA tax exempt that are not addressed in the first and second components addressed above. For example, the IRS may question a transaction where the employer purchases farm products for the purpose of making non-cash payments to an employee, such as the purchase of a finished steer to provide meat as a noncash wage.

When paying employees in non-cash commodities, it is important to recognize that not all payments of “commodity wages” will fall under the same level of IRS scrutiny. An employee that receives meat or milk for his/her family consumption should be safe from scrutiny and reclassification to “cash wages” by the IRS. An employee who is paid in corn, and then uses this corn as feed for his/her own livestock operation, should also be safe from scrutiny. However, the employee that receives a given value of the soybean check as wages will likely be scrutinized during an IRS audit and risks having the wages reallocated as cash wages that are subject to FICA tax. When using commodities as payment keep in mind the guidelines outlined above.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be used as tax advice. It is strongly recommended that you seek council of a tax accountant or tax attorney before using any of this information.

Reviewed by: Sandra Stuttgen and Jenny Vanderlin

Sweat equity and farming

Sweat equity and farming Common strategies to consider for Fair vs Equal

Common strategies to consider for Fair vs Equal Farm asset division a 21st-century conundrum

Farm asset division a 21st-century conundrum What is the biggest threat to a farm estate getting to the rightful heirs? It’s probably not what you think

What is the biggest threat to a farm estate getting to the rightful heirs? It’s probably not what you think