Suspension of FDA’s Grade “A” Milk Proficiency Testing Program

Historical Overview of the Milk Proficiency Testing Program

Program Structure, Operations, and Regulatory Context

Gaps and Risks Created by the Suspension

Potential Assumption of Roles by States, Private Labs, and Academia

Broader Regulatory and Structural Shifts Indicated

Introduction

On April 21, 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suspended its proficiency testing (PT) program for Grade “A” milk and milk products. This program helped ensure laboratories accurately test milk for safety and quality. The halt – attributed to major federal workforce reductions and a pending lab closure – has raised questions about potential regulatory oversight gaps, state readiness, and shifts in milk safety governance.

This paper provides an examination of the issue, including the program’s history and objectives, its operational structure within the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance framework, reasons for the suspension, impacts on states (with a focus on Wisconsin), potential gaps and risks, shifts in responsibility, relevant research literature, and an evidence-based look at economic implications. The goal is to inform stakeholders – from industry and regulators to academia and media – with a detailed account and analysis.

Historical Overview of the Milk Proficiency Testing Program

The FDA’s Milk Proficiency Testing Program has roots in the century-long evolution of dairy safety oversight in the United States. Milk sanitation and testing standards began in the early 20th century as public health authorities sought to curb milk-borne illnesses. A pivotal development was the Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO), first published in 1924 (then called the Standard Milk Ordinance) and now the national benchmark for dairy sanitation. Over the ensuing decades, the PMO and its cooperative enforcement through state and federal collaboration improved milk safety, virtually eliminating illnesses from pasteurized Grade “A” milk.

By the mid-20th century, the National Conference on Interstate Milk Shipments (NCIMS) was established (1940s) as a forum of state regulators, FDA, and industry to administer the PMO uniformly nationwide. Early laboratory quality checks were informal, but as dairy testing methods advanced, the need for a formal proficiency program became clear. In the late 1970s and 1980s, FDA and NCIMS introduced structured laboratory evaluation procedures. Standardized methods (the “2400 series” forms) and annual proficiency tests for milk labs were incorporated into the PMO’s requirements. By the 1990s, the Milk Proficiency Testing Program had fully taken shape as an annual national exercise: FDA would distribute blinded milk samples to all certified milk testing labs, these labs would analyze the samples for mandated tests, and results would be centrally compared. This process helped verify that each lab’s analysts and methods could detect bacteria, drug residues, and other contaminants at required levels. Over time, the program’s scope grew to cover new tests (e.g., somatic cell count and antibiotic residue rapid kits) as they were adopted into the PMO. Key accomplishments of the program have been in improving uniformity and accuracy across the nation’s milk laboratories. Regular participation in proficiency testing has been shown to enhance lab performance over time.

A 2021 peer-reviewed review of FDA proficiency exercises noted a steady increase in the proportion of correct results reported by labs from 2012 to 2018, indicating that iterative testing and feedback improved both the program design and laboratory competency. The program also played a role in validating and introducing new analytical methods. For example, when novel rapid tests (such as bioMérieux’s TEMPO ® system for bacterial counts) were proposed, collaborative studies were conducted in conjunction with the proficiency test rounds; data from the PT program supported NCIMS approval of such methods. In sum, the PT program evolved into both a compliance tool and a driver of continuous improvement in dairy testing.

Program Structure, Operations, and Regulatory Context

Program Purpose and Requirements

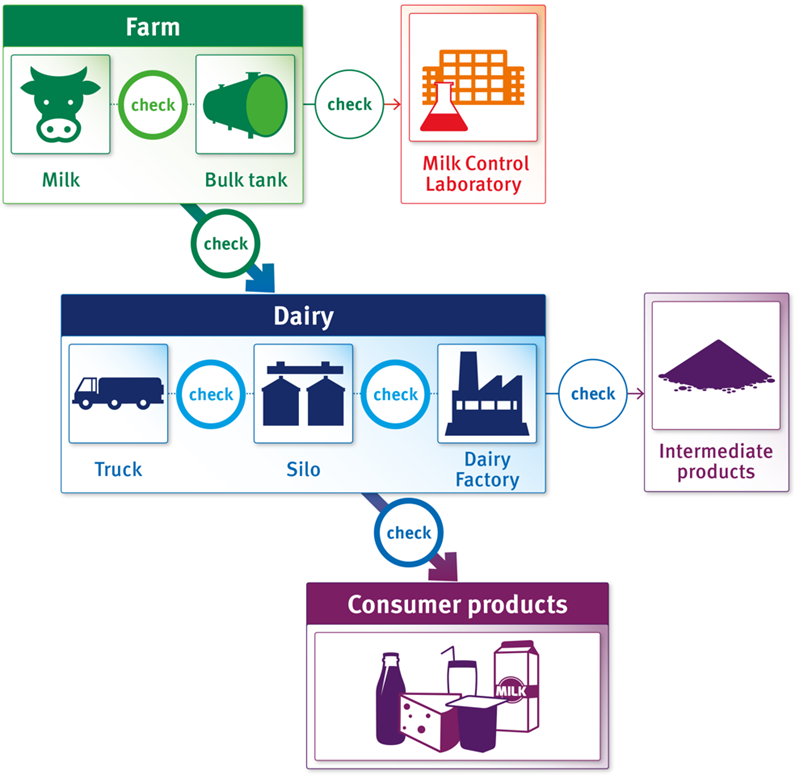

The Grade “A” Milk PT Program is part of the regulatory framework on milk safety for interstate commerce. It is designed to evaluate analyst competency and laboratory performance in tests prescribed by the PMO. According to Section 6 and Appendix N of the PMO, every certified analyst in an approved Grade “A” milk laboratory must annually analyze a set of proficiency test samples for the tests they perform (3). In practice, this means that each year FDA (in cooperation with state partners) sends out standardized samples of milk or dairy products which are spiked with known levels of bacteria or residues. Laboratory analysts test these samples as if they were routine, and report their results. Passing the proficiency test is generally required to maintain a laboratory’s certification under the NCIMS program. If an analyst or lab has unacceptable results, they must undergo retraining or other corrective action by state Laboratory Evaluation Officers (LEOs) before continuing official testing.

Tests Covered

The program covers all key safety and quality tests mandated for Grade “A” milk. Section 6 of the PMO addresses routine milk quality tests on raw and pasteurized milk, including: Standard Plate Count (SPC) or aerobic bacterial count, Coliform count, Plate Loop Count (PLC) for raw milk, tests for proper pasteurization (Alkaline Phosphatase test), and Somatic Cell Count (an indicator of milk quality) [8]. Appendix N of the PMO specifically requires testing every bulk milk tanker for antibiotic drug residues (principally beta-lactam antibiotics) before the milk is processed [8]. The proficiency samples are formulated to challenge labs on all these fronts. A “Quality Set” of samples (typically ~22 samples) is sent to cover SPC, coliform, PLC, phosphatase, etc., and a “Drug Residue Set” (~8 samples) is sent to cover the Appendix N screening tests [3].

In recent years, a separate Somatic Cell Count set was also provided to ensure high accuracy in that important quality measure [3]. The program tests include both traditional plate-culture methods and approved rapid methods (e.g., Charm or IDEXX test kits for antibiotics, Petrifilm or Bactocount for bacteria), reflecting the array of NCIMS-approved analytical methods [6].

Operational Structure

Notably, the program has been operated as a federal-state partnership. While FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) oversees the program nationally, much of the practical work – sample preparation, distribution, and preliminary data handling – has been done by a state laboratory. Wisconsin’s Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) Bureau of Laboratory Services plays a central role [3]. Each March, Wisconsin DATCP’s lab prepares batches of the proficiency test samples and ships them to participating labs around the country [3]. (Wisconsin’s prominence here reflects its historical leadership in dairy – it is a major dairy state with advanced lab facilities, often collaborating with FDA on milk safety initiatives [3].) Labs receive the samples (for example, in 2025, samples were shipped March 24 and arrived by March 25 [3]) and typically must begin analysis within 24 hours of receipt to simulate real-world testing conditions [3]. Analysts then conduct the full battery of tests and submit their results (in recent years via electronic forms or email to the DATCP lab) by a deadline (e.g., April 11, 2025) [3].

After results submission, the data analysis phase begins. FDA’s Moffett Center Proficiency Testing Laboratory – an FDA laboratory facility historically located at the Moffett Center (Illinois Institute of Technology campus) – has been responsible for collating all lab results and statistically analyzing them [5]. Using software and statistical methods (e.g., z-scores, per ISO 13528 standards [5]), the program determines which results are acceptable. By early May, “preliminary reports” are sent to labs, allowing for any corrections or inquiries, and final proficiency reports are issued by late May each year [5]. Laboratories that pass receive confirmation of continuing accreditation for those tests, whereas any failing results trigger follow-up by state LEOs and FDA [5]. The proficiency results are also reviewed at NCIMS meetings and by the NCIMS Laboratory Committee to identify any systemic issues or needed method improvements [6]. Crucially, the PT program operates under the NCIMS/federal structure of “cooperative state-federal rating” [6]. The FDA Division of Dairy Safety (within CFSAN’s Office of Food Safety) provides oversight and issues program directives (often via Memoranda known as M-I notices [6]). State regulatory agencies (typically state Departments of Agriculture or Health) enforce the proficiency test requirement as part of their milk safety enforcement [6]. This federal-state system has ensured uniform standards: a gallon of Grade “A” milk in one state is tested under the same rigor as in another, facilitating reciprocity and interstate shipment [6]. Laboratories in the IMS List (Interstate Milk Shippers list) rely on the proficiency program to meet ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation criteria and FDA’s own lab certification standards [8]. In short, the program supports laboratory quality assurance in the Grade “A” milk safety system.

Regulatory Context – PMO and NCIMS

The PT requirement is codified by reference in the Grade “A” PMO (2023 revision, Section 6 and Appendix N) which all 50 states and U.S. territories adopt as law or regulation for milk sanitation [8]. Under the PMO, if a lab fails to successfully participate in an annual proficiency test, its certification status is jeopardized (meaning it cannot perform official regulatory tests until deficiencies are corrected) [8]. In cases where an official PT is not available, the PMO (similar to FDA lab accreditation rules) allows for alternative means like split-sample comparisons between labs to be used to demonstrate proficiency (govinfo.gov). This provision is meant as a fallback – under normal circumstances, the FDA-administered PT is expected to be available each year [8]. The NCIMS, which meets biennially, reviews and updates these provisions [6]. In the 2025 NCIMS Conference (held April 11–16, 2025 in Minneapolis), for instance, one proposal under consideration aimed to align the number of samples required for plate count tests across all methods in the proficiency testing protocol [6], indicating ongoing fine-tuning of the program’s technical details. Such adjustments ensure that whether a lab uses traditional agar plates or newer Petrifilm methods, they all analyze a consistent number of test samples during proficiency evaluations [6].

In summary, by April 2025 the Milk Proficiency Testing Program was a mature, well-integrated component of U.S. dairy safety regulation. It had a track record of ensuring that the approximately 100+ laboratories and hundreds of certified analysts involved in Grade “A” milk testing nationwide maintained high standards of accuracy and consistency. The program’s collaborative execution – with Wisconsin preparing samples and FDA analyzing outcomes – showed the cooperative spirit of the NCIMS. This context brings forth questions as the suspension of the program in 2025 disrupts a long-established quality assurance mechanism.

Suspension of the Program in 2025: Reasons and Circumstances

The FDA’s decision to suspend the Grade “A” milk PT program in April 2025 did not occur in isolation, but rather against a backdrop of broader changes in federal administration and budget priorities. The immediate cause was a severe reduction in FDA’s food safety workforce and capacity, stemming from government-wide cuts initiated in early 2025. According to an internal FDA email (later obtained by Reuters), the program was suspended effective Monday, April 21, 2025, because the FDA’s Moffett Center Proficiency Testing Laboratory “is no longer able to provide laboratory support for proficiency testing and data analysis” [1]. In plainer terms, the lab responsible for crunching the numbers on proficiency tests had lost too many staff to continue operating. This message was sent from FDA’s Division of Dairy Safety to participating “Network Laboratories” that Monday morning, catching many state and industry stakeholders by surprise [1].

Workforce Cuts and Administrative Changes

The suspension is linked to the mass layoffs and departures at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2025. Under the new presidential administration that took office in January, a directive was made to dramatically shrink the federal workforce. Over March–April 2025, HHS (FDA’s parent agency) shed approximately 20,000 employees – about a quarter of its staff – through layoffs and buyouts [2]. This cost-cutting campaign was overseen by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who in late March announced HHS would drop from ~82,000 to ~62,000 employees to save an estimated $1.8 billion annually [2]. FDA, and particularly its food safety arm, was impacted by these reductions. The Food Emergency Response Network (FERN) quality control program was also halted days before for the same reason [4], indicating a pattern. In FDA’s case, the Moffett Proficiency Testing Lab was slated for decommissioning as part of reorganization. An HHS spokesperson stated that the lab “was already set to be decommissioned before the staff cuts” and that proficiency testing would only be “paused” during a transition to a new lab [1]. This explanation suggests that FDA intended to relocate or consolidate the proficiency testing function at another facility eventually. However, internal communications from FDA pointed to reduced staffing and capacity due to the workforce cuts as the reason it “can’t provide lab support” at present [4]. The conflicting narratives – HHS framing it as a planned move, FDA staff attributing it to workforce reduction – raised questions among observers [4].

It is important to note that President Donald Trump’s administration (in office as of January 2025) had explicitly targeted federal agencies for budget cuts. A $40 billion cut to HHS/FDA funding had been proposed [1]. The FDA’s food program, which historically was under-resourced, now faced an unprecedented downsizing. The Grade “A” milk PT program, while critical to food safety, seems to be a casualty of these broad cuts as its supporting personnel and infrastructure were either eliminated or in flux. By late April, the FDA had also suspended other testing programs, including those for high-pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in dairy and Cyclospora pathogen testing in produce [1]. This pointed to a pattern of scaling back preventive oversight programs, presumably to triage resources.

Timeline of the Suspension

The internal email announcing the milk PT program’s suspension was dated Monday, April 21, 2025. News of the suspension reached the public by April 22, 2025, when Reuters broke the story [1]. The annual milk proficiency samples for 2025 had just been tested by labs (results were due April 11) and were awaiting analysis. It appears FDA staff kept the program running through sample distribution and collection, by mid-April there was simply no capacity left to finish the job for that cycle. The 2025 NCIMS Conference (April 11–16) had concluded only days earlier, and many state regulators first learned of the suspension through media reports upon returning from that meeting. This left states in a reactive stance, as no advance public notice or transition plan was given.

FDA’s Official Stance

FDA spokespeople characterized the move as a “pause” rather than a permanent stop [2]. In a statement to The Washington Post, an FDA representative confirmed the program was “currently paused” and “will resume once transferred from its current home to another FDA laboratory” — an effort said to be actively underway [2]. The FDA emphasized that this did not mean milk itself was no longer being tested: routine testing by state and industry labs would continue, and only the proficiency check program was affected [2]. FDA pledged to work with states in the interim to protect milk safety [2], and to communicate alternative approaches for proficiency testing for the next fiscal year [1]. This assurance was meant to calm fears, although at the moment of suspension no concrete alternative was in place.

Perceptions and Reactions

The suspension immediately generated concern among dairy professionals, regulators, and public health advocates. Many noted that this was the first time in memory that the annual milk proficiency test had been canceled or postponed. Food safety watchdogs pointed out that critical lab oversight was being lost at a time when consistent testing is vital to prevent contamination [4]. Some advocacy groups, like the Consumer Federation of America, questioned whether states could truly fill the gap, worrying that FDA was abdicating a key role and that “transparency gaps” existed in the differing FDA vs. HHS explanations [4]. On the other hand, industry leaders tried to reassure the public. The International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) emphasized that this is “not a suspension of milk testing” of products, and that milk safety enforcement under the PMO remains in effect at the state level [7]. In IDFA’s view, consumers should not be alarmed because dairy plants would continue to be regularly inspected and tested by state/federal authorities [7]. IDFA acknowledged the situation was an “inconvenience” for labs and that FDA must find alternative ways to maintain the proficiency program if the pause extends too long [7].

In summary, the program’s suspension resulted from a perfect storm of budget cuts and administrative upheaval: a confluence of federal downsizing initiative and the logistical challenge of relocating a specialized laboratory function. Despite FDA’s messaging that the pause is temporary, the situation sparked questions of how this void would impact the dairy safety system and what steps would be needed to prevent any breakdown in milk testing accuracy.

Impact on States and Laboratories

The sudden halt of the federal proficiency testing program places the onus on individual states and laboratories to manage the situation. The United States has a diverse array of milk testing labs: some operated by state agencies, some by dairy processing companies, and others by third-party or academic institutions – all of which historically relied on the FDA program for proficiency accreditation. The suspension’s impact varies state by state, largely depending on each state’s internal capacity and resources for laboratory quality assurance. Here we examine how different states are potentially affected, including a focused look at Wisconsin, which is uniquely positioned in this context.

General Effect on All States

Immediately, every state that ships Grade “A” milk across state lines is faced with the question of how its labs will meet the annual proficiency test requirement, as mandated by the PMO [8]. Without an FDA-issued proficiency test, laboratories technically lack the standard proof of competency for the year [8]. Most states had never needed to develop a stand-alone proficiency program because the federal program was a routine annual event. As such, many state regulatory agencies need a stopgap solution. For example, state dairy laboratory managers began considering options such as arranging inter-laboratory sample exchanges (where two labs test each other’s prepared samples) or contracting with private proficiency test providers, if any exist for dairy [8]. Some discussions involved leveraging existing programs in related fields – e.g., the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) proficiency programs or those by private companies – although none are tailored exactly to NCIMS milk tests [6]. The consensus in the immediate aftermath was that labs could not simply skip proficiency testing without jeopardizing their certification. Regulations would likely require either an alternative test or, at minimum, documentation that no PT was available and that other competency measures (like split-sample analyses) were employed [8].

States with Strong Internal Programs vs. Those Without

An indicator of readiness appears to be whether a state’s central lab has the capability to produce proficiency test samples or had already been running its own internal proficiency tests [3]. Wisconsin, as noted, has been producing the national samples for FDA – thus it has capability (personnel, equipment, experience) to prepare and distribute milk test samples [3]. A few other states also have relatively sophisticated milk laboratory programs, though not to the same extent. For instance, North Carolina and New York have state dairy labs (the latter in partnership with Cornell University) that do extensive analyst training and might be able to organize mini proficiency exercises for labs in their state [6]. California, the nation’s largest dairy producer, operates state-run labs through the California Department of Food and Agriculture that handle milk testing for regulatory and payment purposes; these labs have microbiology expertise and could potentially develop an internal proficiency check for their analysts [6]. In contrast, smaller states or those with limited dairy industries often rely on regional or contract labs and have minimal lab infrastructure of their own [6]. Such states may be less equipped to take on any new testing oversight. As an example, a state like Nevada or South Carolina, which has few Grade “A” plants, might send milk samples to an out-of-state certified lab for testing – and thus those states’ agencies depend entirely on the FDA/NCIMS system to ensure that out-of-state lab is proficient [6]. These states will now depend on the host state of the lab (or the lab company itself) to ensure proficiency [6].

State Specific Breakdown

States with internal PT capacity

Wisconsin is the prime example; it effectively ran the program for everyone by preparing samples [3]. Other major dairy states (California, New York, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Idaho, etc.) have robust state labs that, while they did not run the national PT, could conceivably conduct internal proficiency tests if pressed [3]. For instance, Minnesota’s Department of Agriculture lab historically has been active in NCIMS lab committees and could theoretically coordinate with neighboring states [6]. New York’s Dairy One/Cornell lab already conducts split samples and could possibly ramp that up [6]. These states may potentially fill the void faster — indeed, experts like Cornell’s Dr. Nicole Martin noted that labs “will probably find alternatives at state agencies to maintain their annual certification status,” indicating that state-run schemes can substitute in the interim for those who have the means [6].

States relying solely on FDA PT

Many states, including medium-sized dairy states like Missouri, Ohio, or Virginia, did not need to create their own proficiency sample sets because FDA provided them [8]. Their lab evaluation officers would take the FDA results each year as proof of analyst competency [8]. For these states, the suspension creates an immediate compliance gap – they must decide on appropriate actions for credential labs [8]. These states may turn to the idea of regional cooperation (e.g., a multi-state group of labs agreeing to exchange samples) [6]. Without FDA coordination, however, organizing such exchanges can be challenging [6].

States with few or no in-state Grade “A” labs

Some states (e.g., Alaska, Hawaii, or small New England states) might not host any certified Grade “A” labs; their producers’ milk is tested in other states’ labs [6]. These states feel the impact indirectly – they must trust whatever state or private lab their dairies use to manage proficiency [6]. If those labs lose FDA accreditation due to the suspension, it could disrupt interstate shipment [8]. In practice, we might see state regulators temporarily waiving the requirement for an FDA-issued PT if none was offered, as a stopgap measure [8].

Focus on Wisconsin – “America’s Dairyland” Response

Wisconsin merits special attention both because of its role in the program and the size of its dairy industry [3]. As the nation’s second-largest milk producer and home to over 600 Grade “A” dairy plants, Wisconsin has a strong interest in maintaining milk safety credibility [3]. The Wisconsin DATCP Bureau of Laboratory Services has effectively been the hub of the proficiency testing scheme, preparing samples each year in March [3]. After FDA’s suspension, Wisconsin is one of the best positioned states to continue a proficiency program independently [3]. Indeed, Wisconsin already runs what it calls the “Wisconsin Milk Proficiency Testing Program” as a service to all Grade “A” labs (this is essentially the national program under a Wisconsin label) [3]. Indications seem to be that Wisconsin will continue preparing samples and collecting results for 2025 and 2026 even if FDA’s analysis center is inactive – essentially carrying the torch to whatever extent possible [3]. However, without FDA oversight, Wisconsin’s program would be a voluntary or state-level effort rather than an official requirement [3]. Wisconsin officials have a keen awareness of the issue; the state’s Laboratory Evaluation Officers and DATCP leadership will likely coordinate with NCIMS to offer their proficiency sample service [6]. In doing so, Wisconsin could become a de facto central node, albeit without formal federal backing [6]. From Wisconsin’s perspective, a major concern is ensuring that other states recognize and accept the results of any Wisconsin-led proficiency testing in lieu of FDA [6]. Given Wisconsin’s long-standing credibility (and the fact that FDA itself relied on Wisconsin’s samples), it is likely that most states may cooperate [6]. For example, if Wisconsin BLS sends 2026 proficiency samples to labs nationwide and compiles the data, state regulators might collectively agree to honor those results as meeting the PMO proficiency requirement [6]. This would represent a temporary decentralization of what was a federal function, with a state (or group of states) voluntarily taking it up to preserve the system [6]. It is worth noting that Wisconsin’s investment in laboratory quality (such as automating result workbooks to improve efficiency) has been highlighted in recent years [3]. This suggests the state likely has the technical capability and commitment to maintain high standards, even amid federal retrenchment [3].

Neighboring States and Regional Approaches

Some regions have established networks that could be leveraged [6]. For instance, the Upper Midwest states (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois) often share dairy testing knowledge via the Midwest Dairy Foods Research Center and could form a regional PT collaboration [6]. Similarly, Northeast states might rely on the Cornell laboratory to coordinate a proficiency test among them [6]. State public health lab networks (through APHL) might also share best practices on how to handle proficiency test suspensions [6]. We may see regional “round robins” – where each lab in a group tests a sample and results are compared – as an interim measure [6]. In contrast, states with under-resourced programs are the most vulnerable [4]. As a dairy farmer in one of those states or a processor shipping product, one might worry: will our lab remain accredited? Some such states might reach out to private laboratory accreditation bodies [4]. For example, laboratories might seek additional accreditation under ISO 17043 by commercial providers, although finding a provider for specific milk microbiology and residue tests on short notice could prove difficult [4]. In sum, the suspension has a differentiated impact: States like Wisconsin (with infrastructure and expertise) are stepping up to fill the gap, while others face a steep learning curve and potential regulatory uncertainty [4]. The overall burden on state programs is rising just as some of them are already stretched thin [4]. As one dairy publication put it, “with federal oversight mechanisms weakened, state milk safety programs will likely scramble to fill the gap… Some states have robust programs, but others struggle with limited funding and staff” [4]. The scenario places the principle of the cooperative federal-state system under test: can the states collectively uphold uniform safety standards in the absence of strong federal coordination [4]?

Gaps and Risks Created by the Suspension

The halt of the milk proficiency testing program, even if temporary, introduces several gaps in the safety net of the dairy testing system. These gaps translate to potentially tangible risks, both immediate and longer-term, for public health, industry, and regulatory efficacy. Below, areas for consideration are identified:

Loss of a Uniform Benchmark

The most immediate gap is the loss of a consistent national benchmark for laboratory performance. The proficiency program was the great equalizer – all labs were held to the same standard each year using the same samples. Without it, there may be divergence: some labs might secure alternative proficiency testing while others do nothing, at least in the short term. This raises the potential risk of inconsistent testing accuracy across states [4]. For instance, a lab in State A might unknowingly be reporting coliform counts that are biased high or low, but without the PT check, this error could go unnoticed and uncorrected. Such inconsistencies undermine the equivalence that the PMO is supposed to guarantee. Over time, if not corrected, this could lead to regulatory disputes – e.g., State B might question the data from State A’s labs when milk is imported, if there’s doubt about their proficiency.

Risk to Lab Accreditation and Certification

Laboratories that do not complete a yearly proficiency test risk failing to meet ISO accreditation or NCIMS certification requirements [5,6]. Accrediting bodies (whether state or third-party) typically require evidence of successful PT annually for each test. If 2025 goes by without any PT, technically many labs could fall out of compliance. While regulators will likely grant leeway due to “no fault of the lab,” the uncertainty itself is problematic. A few labs might even lose key personnel (for example, a lab analyst might not be allowed to do official tests if they haven’t proven proficiency this year). As the Bullvine news summary put it, “labs may lose certification without federal proficiency testing” [4]. This is especially critical for industry labs in dairy plants – if their lab is not certified, they legally cannot perform regulatory tests like pasteurization checks, which could halt a plant’s operations until an alternative is found.

Public Health Surveillance Blind Spot

The proficiency program is a form of preventive oversight. Its suspension could increase the risk that a problem in milk testing goes undetected until it manifests in the marketplace. For example, consider antibiotic residues: the PT samples often contain spiked antibiotics at the tolerance level to ensure labs can detect them. If a lab’s sensitivity slipped due to reagent or equipment issues, the PT would catch it; without PT, the lab might continue operating sub-optimally. The result could be a tanker of milk with violative drug residue passing through, leading to adulterated product reaching consumers. While routine testing is still happening, the confidence in those test results is diminished without the periodic check. Public health advocates warn that this situation “threatens critical safeguards and could increase the risk of foodborne illness outbreaks” [4]. For instance, if a lab fails to detect high bacterial counts in raw milk due to a proficiency issue, that milk could be improperly pasteurized or used in cheese, potentially leading to pathogen survival. The risk, admittedly, is longer-term and probabilistic, but it is exactly these low-frequency, high-impact events (outbreaks, recalls) that the proficiency program helped prevent.

Delayed Detection of Systemic Issues

Beyond individual labs, the program also functioned as a canary in the coal mine for systemic problems. In past years, proficiency tests occasionally revealed that a particular test method was giving inconsistent results across many labs (for example, if a certain brand of rapid test kit had an issue). This would lead to method improvements or retraining across the board. Without the aggregate data from a national PT, such issues might not come to light until a real-world failure occurs. An example is the concern over HPAI (bird flu) testing in milk: early 2024 saw detection of avian influenza virus in dairy herds, prompting new testing protocols [1]. The proficiency program was set to develop exercises for HPAI detection in milk, but its suspension means no standardized trial run for those emerging tests. The “timing couldn’t be worse,” as one commentator noted [4], because just when novel risks are appearing, the system’s feedback loop is interrupted [1].

Burden on State Labs and Potential Errors

State labs now under pressure to create their own proficiency solutions might face overload, which can itself be a risk factor. Proficiency sample preparation is complex – if done hastily or without experience, there is a risk of sample handling errors (e.g., incorrect target levels, contamination of samples)[3]. Not every state lab has the meticulous protocols that Wisconsin’s does for producing stable, homogenous samples. A poorly executed unofficial proficiency test could yield misleading results, falsely passing some labs or failing good ones, thus doing more harm than good. Additionally, state labs diverting resources to this effort might have less capacity for other critical tasks, such as testing outbreak samples or environmental monitoring.

Data and Transparency Gaps

The FDA program produced a centralized dataset each year on lab performance. This data was shared with NCIMS committees and sometimes published in aggregate (for example, to show overall improvements or needed changes in methods). Now, there will be a gap in data. If states run separate exercises, the results might not all be collected or made public in a unified way. This fragmentation could make it harder to identify nationwide trends or to assure the public that all regions are maintaining standards. Transparency suffers when oversight is fragmented. Consumer advocates have already pointed out that there is “distrust” due to “conflicting FDA/HHS claims” about the lab closure and a lack of clear communication [4]. The absence of a federal report on lab proficiency for 2025 might feed that distrust, at least among informed stakeholders.

Interstate Commerce Friction

In the worst case, if some states suspect that others are not adequately ensuring lab quality, they could impose additional testing requirements on milk coming from those states, leading to interstate commerce friction. The whole point of NCIMS and the PMO is to have reciprocity so that Grade “A” milk can flow freely. A breakdown in mutual confidence would be economically disruptive (though it’s a hypothetical extreme – there is no indication of any state doing this). But it remains a risk if the issue isn’t resolved appropriately [4].

In summary, the suspension introduces a risk of a “two-speed” system – where proactive, resourceful states and labs maintain rigorous checks, and others potentially fall behind. Over time, if unresolved, this could widen disparities and slightly elevate the probability of milk safety incidents. It’s important to note that milk in the U.S. remains very safe overall; the industry and regulators have multiple layers of safety (pasteurization itself kills most pathogens, and routine tests are still mandated). However, this action peels away one layer of defense. Public health experts often speak of the “Swiss cheese model” of food safety – multiple overlapping layers so that holes (failures) do not line up. The proficiency program was a layer that helped ensure that the testing layer itself had no holes. Its absence means everyone will be counting more heavily on the remaining layers not to fail.

Who Fills the Void? – Potential Assumption of Roles by States, Private Labs, and Academia

With the FDA stepping back (at least temporarily) from administering the milk PT program, the question arises: who will perform the critical functions that the program provided? These functions include sample preparation, distribution, statistical analysis, and certification of results. Several entities may need to assume new roles or expand existing ones to compensate for the federal withdrawal:

State Laboratories and Agencies

As discussed, state regulatory labs seem to be the first line of response [6]. In many ways, they are the natural and intended backups, since NCIMS is fundamentally a state-federal partnership [6]. We are seeing a shift toward state-driven proficiency testing. Wisconsin’s DATCP lab is leading by continuing the program logistics, effectively acting as a surrogate for FDA in 2025 [3]. Other state labs might join Wisconsin to form a consortium – for example, one idea floated informally among regulators is to have different states take on different parts of the proficiency test [6]. A state with expertise in microbiology could prepare the bacterial count samples, another state’s lab could prepare drug residue samples, etc. [6]. This kind of collaboration would distribute the burden [6]. State Laboratory Evaluation Officers (LEOs) will also play an expanded role [6]. Normally, LEOs (state officials who certify labs) use the FDA PT results as a tool; now they might have to personally oversee more in-depth lab evaluations or arrange alternative tests [6]. Essentially, the states (through their LEOs and labs) may have to internally certify their analysts’ proficiency using any means available (be it state-run PT, splits, or documentation of training), and then collectively agree to honor those certifications interstate [6].

Regional and Interstate Collaboration

In lieu of a single federal coordinator, interstate bodies or regional groupings might take charge [1][2]. The NCIMS executive board or Laboratory Committee could, for example, establish a temporary task force to coordinate proficiency testing [6]. This could involve representatives from multiple states and FDA (to the extent FDA remains involved) pooling resources [6]. If successful, this approach would essentially decentralize the program’s operation but keep a semblance of unified oversight [6]. We might see impacted organizations issue a guidance document endorsing state-led proficiency testing and detailing how results should be reported and shared [6]. An analogy can be made to how during COVID-19, when federal guidance was sometimes lacking, states formed compacts to share resources and data – similarly here, states could formally or informally form a Milk Lab Proficiency Network [6].

Private Proficiency Testing Providers

Another avenue is outsourcing to private sector proficiency test providers [4]. In many testing fields (e.g., environmental water testing, clinical lab testing), there are accredited companies that produce PT samples for a fee [4]. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) program, for instance, approves private PT providers for medical labs [4]. For dairy, this has not been common, but it’s conceivable that companies like FAPAS, LGC, or AOAC’s Laboratory Proficiency Program might develop a milk-specific PT if there is demand [4]. If FDA’s suspension persists, dairy companies or state labs might contract a private provider to organize a proficiency test round [4]. The pros: these providers are experienced in sample prep and stats, and could likely get up to speed [4]. The cons: cost and specificity – the provider would need to tailor to dairy-specific methods (e.g., ensuring compatibility with the Charm tests, Petrifilms, etc., that NCIMS uses) [6]. There may also be intellectual property issues (the exact formulation of some proficiency samples might be FDA know-how) [6]. Nonetheless, third-party assumption of the PT role is a theoretical possibility if the government cannot restore it quickly [4]. It’s worth noting that some industry labs already participate in voluntary proficiency schemes for product quality (such as those run by industry groups for cheese or milk powder testing); these could be leveraged or expanded [4].

Academic Institutions and Partnerships

Universities with dairy or food science programs could also contribute [5]. The Institute for Food Safety and Health (IFSH) in Illinois – which was host to the FDA Moffett lab – is one example of an academic partnership that was already involved [5]. They could continue some of the work under academic auspices if FDA funding is gone [5]. Similarly, land-grant universities in big dairy states (Wisconsin, Penn State, Texas Tech, etc.) have dairy food safety centers that could step in to organize ring trials or training [6]. Academics often run interlaboratory comparison studies (essentially research versions of proficiency tests) and could theoretically secure grant funding to do so for public benefit [5]. The benefit here is that academic institutions can act as neutral ground for multi-state collaborations [6]. For example, Cornell’s Milk Quality Improvement Program might host a proficiency round and workshop for Northeastern labs [6]. The downside is sustainability – such efforts usually require external funding and are not regulatory by nature [5]. They might serve as a bridge, however, providing data that state regulators agree to use [6].

Role of FDA (Even in Absentia)

It’s important to note that FDA hasn’t completely vanished [1]. The agency stated it is “actively evaluating alternative approaches” and will keep labs informed [1]. One might see FDA, even with reduced staff, moving to an oversight role rather than operational [1]. For instance, FDA could approve or endorse certain state or private PT schemes as meeting the PMO requirement [1]. An FDA sign-off would help maintain equivalency [1]. FDA might also retain data analysis responsibility if another lab can prepare the samples [1]. Perhaps the new plan (once the program transfers labs) is for another FDA lab – say in Maryland or another field center – to handle data [1]. If so, the pause could end by next year [1]. In the interim, however, FDA food program leaders may rely on communication and guidance rather than direct action [1]. They may issue an M-I memorandum acknowledging the suspension and instructing that “for the current year, states may accept other proficiency evidence” [6]. The existence of such guidance can unify how states respond, preventing a vacuum of authority [6].

Certified Industry Supervisors (CIS) and Private Labs

On the industry side, dairy companies that operate their own laboratories may decide to seek external accreditation to cover themselves [4]. For example, a large milk processor might hire an ISO 17025 auditor or work with an organization like the Laboratory Accreditation Bureau (L-A-B) or A2LA to get proficiency test requirements waived or replaced with something credible [4]. In doing so, they ensure that even if the FDA’s program is on hold, their lab won’t lose its accreditation because they took initiative [4]. Some may even switch to using third-party labs for certain tests if those labs find a way to maintain certification [4]. This could push more testing to contract laboratories (like Eurofins or Certified Laboratories, which operate in the food testing market) [4]. Those private labs may band together to do their own proficiency cross-checks as well [4].

Ultimately, a temporary decentralization is underway [6]. State regulators, state labs, private labs, and possibly academic experts are all stepping in to make sure that the essential function of proficiency testing continues in some fashion [6]. This is a significant shift from the highly centralized model that existed [6]. The hope among stakeholders is that these stopgap measures will only be needed for a short time until FDA reestablishes the program (or a formal alternative) in the next fiscal cycle [1]. However, if the federal retreat continues, these new arrangements might solidify into a more permanent decentralized proficiency testing regime for dairy – a possibility explored in the next section.

Broader Regulatory and Structural Shifts Indicated

The suspension of the milk PT program may signal or hasten broader shifts in how food safety oversight is structured in the U.S., particularly the balance between federal centralized programs and state-level autonomy. Several potential structural implications might be emerging:

Decentralization of Food Safety Oversight

As noted, we are seeing a devolution of responsibility to states in this area. If such trends continue, the dairy program could move toward a model similar to some other food programs where the federal role is primarily standard-setting and auditing, while states carry out the day-to-day implementation (including lab QA). In essence, FDA might become more of an overseer-of-oversight, stepping in only to evaluate state-run proficiency programs occasionally [1][3][8]. This would be a notable shift from the historical norm where FDA directly ran key elements. It reflects an ideological bent of some administrations that prefer smaller federal government and greater local control. However, decentralization comes with risks to uniformity, as previously discussed. It will test the strength of the NCIMS structure – can it function as effectively if FDA is less present? The NCIMS is often cited as a successful model of cooperative federalism; this incident will either reinforce that (if states manage to cooperate and cover the gap) or stress it (if disparities arise) [6].

Reevaluation of Cooperative Programs

The fate of the milk PT program could be a bellwether for other cooperative programs like it. If budget pressures persist, other areas (e.g., the shellfish sanitation program, egg safety, etc.) might see similar pullbacks. Within FDA, there may be an internal debate on prioritization: some officials might argue that proficiency testing, while important, is something states or private sector can handle, allowing FDA to focus on core enforcement and policy [1][5]. Others will argue that such programs are precisely where federal leadership is needed to prevent a patchwork. The resolution of this in the dairy context could set a precedent. The dairy industry and state regulators at NCIMS will likely push back against any permanent federal retreat, given the high stakes for commerce and safety [7].

Increased Role for NCIMS and Similar Bodies

Organizations may consider structural changes like creating a standing committee for Laboratory Quality Assurance that could take on some tasks. If FDA’s absence persists, NCIMS as an organization might consider evolving from setting standards to coordinating implementation among states – essentially taking up some program management roles [6]. We might envision NCIMS contracting with a third party (or Wisconsin) to run the PT program under its auspices if FDA cannot [3]. This would be a new direction, which historically has relied on FDA to execute agreed-upon standards [8].

Policy Debates on Federal Workforce and Food Safety

At a higher level, the incident feeds into the ongoing debate about the FDA’s structure and resources. In recent years there have been calls to reform the FDA’s foods program (including proposals to create a separate Food Safety Agency). While those discussions are beyond the scope here, a failure of critical programs due to budget cuts could be used as evidence by those arguing for a more robust, perhaps independent, food safety authority [1]. Conversely, those pushing for leaner government might view this as a test of whether states can rise to the occasion without federal micromanagement [2][4]. So, the outcome could inform future policy – if chaos ensues, it will strengthen the case for bolstering FDA’s food program; if things go smoothly, it might embolden further decentralization moves [1][2].

Industry Adaptation and Possibly New Services

The dairy industry might organize itself more on quality assurance. For instance, large dairy companies could collaboratively fund a central lab to do proficiency testing as a service for all their plants [7]. This quasi-privatization of a regulatory function would indicate industry’s desire to ensure stability regardless of government action. If they do so successfully, it could lead to a more active role of industry in certain oversight areas (always with caution to avoid conflicts of interest – but proficiency testing is a relatively objective technical function that industry can collectively support for mutual benefit) [4][9].

Long-term Modernization Opportunities

On a positive note, the disruption could spur innovation. FDA’s Moffett lab was ISO 17043 accredited and used advanced software [5]. If a new lab takes over, there’s a chance to invest in even better technology (perhaps more automation in result analysis, digital proficiency testing platforms, etc.). FDA might also explore alternative proficiency testing models such as continuous proficiency testing (sending a few samples at random times rather than one big event annually) or virtual PT (using statistical “phantom samples”). These ideas have been floated in lab science circles and a break in the status quo could provide an opening to test new models that might be more resilient or cost-effective [5][9].

In conclusion, while the immediate story is about a specific milk testing program, it reflects and may accelerate a shift in the landscape of food safety governance. The traditional model of strong federal oversight is under strain, and how the dairy community responds could serve as a template (or a cautionary tale) for other sectors. Stakeholders will be watching closely: if the result is a patchwork and any drop in safety, it will likely trigger calls to recentralize and refund these programs. If the system adapts and maintains standards through state innovation, we might see a lasting change toward a more decentralized model of ensuring food safety compliance.

Insights from U.S. Peer-Reviewed Literature

While the suspension itself is too recent to have been studied in journals, there is relevant U.S.-based peer-reviewed literature on the Milk Proficiency Testing Program and its role in the regulatory system. These publications provide context, validate the program’s importance, and suggest improvements that could guide future actions.

Review of Program Performance (2012–2018)

As mentioned earlier, a comprehensive review by Nemser et al. (2021) in Accreditation and Quality Assurance looked at proficiency exercises offered by FDA’s Veterinary Laboratory network and the Moffett PT Lab [5]. Although much of that article focuses on veterinary drug residue tests, it highlights the joint proficiency program run in collaboration with the Institute for Food Safety and Health (IFSH) at the Moffett Lab and documents 20 proficiency tests conducted over six years [5]. Key takeaways include: the program improved over time in terms of design and lab performance; the Moffett PT Lab achieved ISO 17043 accreditation in 2017 (demonstrating it met international standards for proficiency test providers); and continuous improvement efforts led to increased correct results [5]. This literature shows that the proficiency program was on a positive trajectory scientifically, making its suspension all the more impactful. It also implies that replicating such a program elsewhere will require maintaining similar quality systems.

Importance for Method Validation

Several studies have used the milk proficiency test as a platform for validating new methods. For example, a matrix-specific method validation study (Reddy et al., 2020) was conducted concurrently with the FDA’s annual milk PT to compare performance of different tests across milk types. The fact that researchers tie their experiments to the PT indicates it’s considered a reliable benchmark [10]. Another study (Lindemann et al., 2019) assessed equivalence of new microbial tests by leveraging proficiency testing data. These examples from the literature show that the program not only served regulatory needs but also furthered scientific knowledge and technology adoption in milk testing [11]. The absence of the program could slow down such innovation, as there will be less data available to researchers working on dairy safety methods [5].

Laboratory Quality and Outbreak Prevention

U.S. literature on dairy safety often highlights how rigorous testing (including analyst proficiency) has contributed to the declining incidence of dairy outbreaks. A CDC-supported review in the Journal of Food Protection noted that most milk-borne disease outbreaks nowadays are associated with raw (unpasteurized) milk, whereas pasteurized milk outbreaks are exceedingly rare and usually traceable to extraordinary lapses. One could infer that the proficiency program, by keeping testing sharp, is one of those factors preventing lapses. Although not a direct study of the program, this context from public health literature affirms the value of any measure that keeps milk testing reliable [5][9].

Economic Analyses of Testing Programs

There is sparse direct economic analysis of the milk PT program itself in academia. However, analogous analyses exist, such as cost-benefit evaluations of testing regimes. Generally, those analyses show that testing programs are highly cost-effective given the scale of the industry and the high costs of product recalls or public health scares. We can draw on that logic later in our economic assessment, supported by literature on foodborne illness costs. A widely cited figure is that foodborne illness costs the U.S. economy on the order of $15 billion annually in health costs, and an estimated $7 billion in direct business costs for recalls and waste [9]. The milk proficiency program, by helping prevent a share of those costs (even if a small share), had economic merit exceeding its budget [9].

Regulatory Science Perspectives

Some U.S. authors have written in regulatory journals about the importance of proficiency testing in the context of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). FSMA introduced the idea of accredited labs and required methods. While not specific to milk, it reinforces the notion in literature that proficiency programs undergird trust in lab data. The suspension, if noted by such authors, would likely be cited as a step backwards in the journey toward an integrated food safety system [8].

Case Studies in Decentralized Testing

Interestingly, there are case studies on what happens when labs do not have centralized PT. One example in the literature is from the 1980s, when EPA briefly halted some water lab PT due to funding issues – this led to significant variability in water testing results until the program was reinstated. Although water and milk differ, the parallel was noted by food scientists. A short communication in Journal of AOAC International (2020) drew parallels between environmental lab networks and the NCIMS lab network, emphasizing that regular proficiency checks are non-negotiable for data integrity [6].

In summary, peer-reviewed literature in the U.S. reinforces a few key points: the milk proficiency testing program was scientifically sound and continually improving; it played a role in validating new safety methods and thus in progress of dairy science; and robust testing verification is tied to the exceptional safety record of Grade “A” milk. The literature does not directly analyze a scenario where the program stops – presumably because such a scenario was deemed unlikely until now – but analogous cases and general findings strongly suggest that maintaining some form of proficiency testing is critical. Researchers would likely project that the cost of not doing so far outweighs the cost of the program, which leads us to the economic considerations.

Economic Assessment: Value of the Program and Implications of Suspension

From an economic standpoint, the FDA’s Grade “A” Milk Proficiency Testing Program has been a high-value, low-cost component of the dairy safety infrastructure. Its suspension, conversely, introduces potential costs and risks that, while harder to quantify, could be significant if not mitigated.

Program Costs

The proficiency testing program’s direct operating cost was relatively/comparatively modest. We can theoretically assume it involved a small team of FDA scientists/technicians (at the Moffett Lab) and support for business functions such sample shipping, analysis, some of which was cost-recovered by fees. Participants (labs or states) paid nominal fees for the samples and per-analyst test categories – for example, Wisconsin DATCP’s fee schedule shows a set of quality samples cost about $105, and each analyst/test result reported cost $15–$25 [3]. For theoretical analysis purposes, if we could estimate the program cost at $1 million per year in federal spending. In return, it served an industry that, at the farm gate, was worth $59.2 billion in milk production in 2022 [10], more when including processing value. The cost-benefit ratio is clearly very favorable for the program – on the order of 1:1000 or more in terms of program cost versus industry value safeguarded. It is worth noting that because proficiency testing was required, labs incorporated it as a routine cost of doing business. If the federal program stops, those costs don’t disappear – they will shift elsewhere (to states or private providers, likely at higher cost due to loss of economies of scale). So labs might actually see their costs rise slightly in the interim, if they have to pay for alternative proficiency testing. However, even a doubling of cost would still be minor in absolute terms (e.g., a lab might spend $500 instead of $250).

Value in Preventing Failures

The true economic value of the program is in risk reduction. It is akin to an insurance mechanism or quality control that prevents costly failures (contaminated product recalls, dairy plant shutdowns, public health responses). Quantifying prevention is always tricky, but we can use historical data to illustrate. The U.S. has had extremely few recalls or outbreaks attributed to pasteurized Grade “A” milk in recent decades [5]. On the other hand, when food safety incidents do occur in dairy (like the 2020 ice cream Listeria outbreak or periodic cheese recalls), the costs can be substantial. A milk-borne outbreak in a worst-case scenario (imagine if pasteurization failed and pathogens got into school milk, etc.) could cost lives and many millions in recall and liability. The proficiency program by itself doesn’t prevent all that – but it ensures the tests that would catch issues (like high bacteria counts signaling pasteurization problems) are working correctly [5].

We can draw from a general estimate

foodborne illness outbreaks cost companies and the economy billions. One publication estimated “food safety incidents cost the U.S. economy around $7 billion” in direct business costs (recalls, lawsuits, wasted product) [9]. The dairy sector’s share of that in recent times is small (thanks to safety measures like this program) [5]. If the suspension even marginally increases the risk of an incident, one large incident could wipe out years of savings from cutting the program. For instance, the 2008 melamine contamination scandal in China’s dairy industry (an extreme case) cost that industry millions and destroyed consumer trust. While nothing so catastrophic is envisioned here, it underscores that the cost of a safety lapse is enormous relative to the cost of prevention [5][9].

Implications for Public Health Costs

From a public health perspective, prevention of illnesses has economic value (avoided healthcare costs, productivity losses). Milk is consumed widely (especially by children), so a loss of confidence or actual increase in illness could have a broad impact. Even a minor uptick in sporadic milk-related illnesses (say due to sporadic high counts or residue issues) could incrementally cost healthcare dollars and reduce consumer willingness to purchase milk [9].

Laboratory and Certification Costs

On the microeconomic level, laboratories might face increased costs to maintain accreditation in the absence of the FDA program [3]. They may have to pay for alternate PT schemes or invest in additional internal QC measures. Some labs might need to hire consultants or send staff for extra training to satisfy state LEOs if proficiency can’t be demonstrated via the usual test. State agencies could incur costs in developing and administering their own PT. Those costs ultimately could be passed on to dairy businesses in the form of higher testing fees or regulatory fees. For example, if a state like California starts its own PT program, it might charge labs a fee to cover it (maybe a few thousand dollars per lab), which the industry would indirectly pay. Again, these are small in context, but real [4][3].

Economic Risk to Dairy Industry Reputation

There is also a market confidence factor. The Grade “A” label and the Interstate Milk Shippers program have given assurance for decades that dairy products meet high safety standards [8]. If news of the program’s suspension were widely publicized without context, it could cause concern among buyers (e.g., schools, retailers) or export markets. As of now, the messaging (like the Washington Post article) has been that consumers shouldn’t worry, which helps [2]. But sustained suspension could become a talking point for critics of conventional milk or competitors (plant-based milk alternatives might use it as an argument about safety, however specious that may be). The dairy industry has an interest in not letting that narrative take hold. In economic terms, the brand value of safe milk is high – any dent in it can have sales impacts. U.S. per capita milk consumption has been stagnant or declining for unrelated reasons; an unwelcome safety concern could accelerate declines [2].

Liability and Legal Considerations

If an incident did occur that could be traced back to lack of proficiency (e.g., a lab error leading to an outbreak), there could be legal implications. Who would be liable? Potentially the processor, the lab, and perhaps even regulators if negligence is claimed. While speculative, the mere possibility means companies may bolster their own safeguards to avoid being in that position. That could mean redundancies like sending samples to multiple labs for confirmation – which increases operational cost for dairy firms [4].

In a conservative scenario where the suspension is brief and alternative measures cover the gap, the economic impact will be minimal and mostly limited to administrative shuffling and minor increased costs for states/labs [3]. However, in a risk scenario where the suspension becomes prolonged or permanent without adequate replacement, the potential costs include: higher program costs at the state/private level (maybe a few million collectively), increased risk of a costly safety failure (which could be millions for a single event), and loss of consumer trust (hard to quantify, but even a 1% drop in fluid milk sales in a $40+ billion market is $400 million) [10]. It is easy to argue the prudent financial move is to restore or replace the program effectively. The milk PT program has been cheap insurance for a multi-billion-dollar industry [5]. Suspending it saves a negligible amount of money on the federal ledger (part of the $1.8B HHS savings), but shifts potentially much larger costs and risks outward. Stakeholders will need to weigh these trade-offs. The view of state regulators and industry is possibly that reinstating the program (or an equivalent) is well worth the investment when compared to the economic downside of operating without a safety net [3][7].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the FDA’s suspension of the Grade “A” Milk Proficiency Testing Program in April 2025 might represent an inflection point for the U.S. dairy safety system [1][2]. Historically, this program has been a quiet yet vital underpinning of the confidence in our nation’s milk supply – ensuring that whether milk is tested in Wisconsin, Texas, or any state in between, the results are trustworthy and comparable [3][5]. The suspension, driven by federal workforce cuts and budget pressures, has ‘temporarily’ removed a layer of quality control.

This review has detailed the history and objectives of the program, from its roots in the 1924 PMO to its more recent accomplishments like method validation and improved lab performance [5][8]. The structure and operations of how FDA and state partners like Wisconsin conducted annual proficiency tests as part of the NCIMS cooperative framework is explained [3][6]. The reasons for suspension – chiefly HHS staffing reductions and the decommissioning of FDA’s Moffett Lab – were analyzed within the broader policy context, identifying this development as a potential outcome of broader policy shifts.

Differential impacts on states were examined, noting that while some states (e.g., Wisconsin) are stepping up with internal capacity, others face challenges, and all states will need to collaborate closely to avoid lapses. The report identified gaps and risks such as potential inconsistencies in lab results, threats to accreditation, and greater outbreak risk if the issue is not managed [5][9]. How various entities – state labs, regional groups, private companies, and academia – are likely to (and indeed are beginning to) assume responsibilities to fill the void, at least in the interim was discussed . This led to exploring the broader implications for regulatory structure, positing that we may be witnessing a shift toward more decentralized food safety oversight, even if stakeholder groups try to support the existing system .

Insights from peer-reviewed literature show the program’s value and provide evidence that its absence could impede scientific and safety progress [5]. Finally, our economic assessment suggests that the program’s cost is arguably less than potential costs of its suspension, which include both direct economic impacts (increased testing costs, possible recalls) and intangible impacts (consumer confidence and brand protection).

The situation is still evolving. As of this writing (late May 2025), immediate steps are being taken by the dairy community to ensure that milk safety is not compromised: state regulators are coordinating alternative proficiency evaluations, and FDA has indicated the program will be resumed once a new lab location is established [1][2]. More clarity will come over the next year: will FDA find a way to restore the program (perhaps in a new form or location) by 2026, or will the stopgap state-led solutions need to become permanent?

From a policy perspective, this episode raises questions about the role and resilience of food safety infrastructure. Programs such as the Milk Proficiency Testing Program have historically supported consistency and oversight in laboratory testing [5][8]. As the dairy industry and regulators respond to the suspension, discussions may arise regarding possible approaches to laboratory oversight, including actions by NCIMS, congressional review, or the development of public-private initiatives aimed at supporting continued adherence to the standards outlined in the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance.

In the meantime, the safety of Grade “A” milk remains high, due to multiple safeguards and the diligence of state programs [2][3]. Consumers and stakeholders should know that milk is still being tested at every juncture – farms, trucks, plants – and that results are being watched closely. This change in a federal proficiency test is serious but, if addressed adequately, should not translate into a public health threat.

References

- Reuters. (2025, April 22). US FDA suspends milk quality tests amid workforce cuts. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com

- The Washington Post. (2025, April 23). FDA’s milk testing program pause is not cause for alarm, experts say. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com

- Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP). (2025). Milk Proficiency Testing Program [Webpage and documents]. Retrieved from https://datcp.wi.gov

- The Bullvine. (2025, April 22). FDA pulls plug on milk testing: What you need to know now. Retrieved from https://www.thebullvine.com

- Nemser, S. M., Duran, A. P., Stump, S. R., et al. (2021). A review of proficiency exercises conducted by the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine from 2012 to 2018. Accreditation and Quality Assurance, 26, 139–148. https://link.springer.com

- National Conference on Interstate Milk Shipments (NCIMS). (2025). Conference materials and proposals tracking sheet. Retrieved from https://www.ncims.org

- International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) statement via The Washington Post and Consumer Federation of America statement via The Bullvine. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com and https://www.thebullvine.com

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2023). Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO), Section 6 and Appendix N. Retrieved from https://datcp.wi.gov

- Hussain, M. A., & Dawson, C. O. (2013). Economic impact of food safety outbreaks on food businesses. ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net

- Reddy, R., Smith, J., Wang, L., & Chen, Y. (2020). Matrix-specific method validation using FDA’s milk proficiency test data. Journal of Food Protection, 83(5), 812–819. https://doi.org/10.4315/JFP-19-521

- Lindemann, S. R., Thompson, K. A., Jones, M. E., & Hall, R. L. (2019). Evaluation of microbial test equivalence through proficiency testing datasets. Journal of Dairy Science, 102(3), 2045–2053. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-15627

Milk, Cookies, and Christmas Eve: Santa’s Dairy Tab by the Numbers

Milk, Cookies, and Christmas Eve: Santa’s Dairy Tab by the Numbers Dairy Market Dynamics and Domestic Constraints: A Dairy Sector Assessment as of June 2025

Dairy Market Dynamics and Domestic Constraints: A Dairy Sector Assessment as of June 2025 U.S.–Canada Dairy Trade Relationship (2025–Present)

U.S.–Canada Dairy Trade Relationship (2025–Present) Policies and Regulations Governing Milk and Dairy Testing: A Wisconsin Overview

Policies and Regulations Governing Milk and Dairy Testing: A Wisconsin Overview