U.S.-Canada Dairy Trade Agreements:

A Historical and Economic Review

Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement

U.S.-Canada Dairy Trade Timeline

Trade Agreements across U.S and Canada

Comparative Economic Analysis of Dairy Trade

Trade Disputes and Enforcement Mechanisms

Successes and Failures Across Agreements

Introduction

The dairy trade between the United States and Canada has long been shaped by a series of trade agreements and international rules, each influenced by the unique sensitivities of the dairy sector. In Canada, a supply management system tightly regulates dairy production and imports to support farmer incomes, leading to high tariffs and quotas on dairy imports. U.S. dairy producers, who face more market-oriented conditions, have sought greater access to Canada’s protected market.

This review examines the evolution of U.S.-Canada dairy trade through major agreements – from the 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) to the current United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) – as well as multilateral frameworks like the World Trade Organization (WTO). It analyzes the political and economic context behind each agreement, key dairy-specific provisions (such as tariff-rate quotas and market access commitments), the economic outcomes (trade flows, prices, and industry competitiveness), notable successes or failures, and the legal disputes that have arisen. Lessons are then drawn for future trade policy in the dairy sector.

Table 1. U.S.-Canada Dairy Trade Relationships

|

Year

|

Event

|

|---|---|

|

1947

|

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) established; global trade rules, agriculture mostly exempt (dairy protected)

|

|

1966

|

Canadian Dairy Commission created

|

|

1972

|

Canada implements national dairy supply management (quotas & price controls)

|

|

1989

|

CUSFTA (Canada-US FTA) in force; Dairy exempt from tariff cuts; quotas remain

|

|

1994

|

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) replaces CUSFTA; Canada retains dairy import barriers

|

|

1995

|

WTO Agreement on Agriculture: Dairy import quotas, TRQs, high tariffs (200%+)

|

|

1997

|

WTO case: US/NZ vs Canada dairy (challenge export subsidies)

|

|

1999

|

WTO rules Canada’s special milk classes are illegal export subsidies

|

|

2003

|

Canada ends export subsidy scheme; WTO dispute settled

|

|

2017

|

Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA): Canada-EU trade deal; ~18.5k tonnes EU cheese import quota

|

|

2017

|

Canada introduces Class 7 pricing (low-price milk ingredient class)

|

|

2018

|

USMCA (North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) 2.0) negotiated; Canada to eliminate Class 7, expand US dairy access (~3.6% market)

|

|

2018

|

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)-11) signed; Canada opens ~3.3% dairy market to TPP partners

|

|

2020

|

USMCA enters force; Class 7 eliminated; new US dairy TRQs start

|

|

2022

|

USMCA Panel 1: rules Canada TRQ allocation violates USMCA (US win)

|

|

2023

|

USMCA Panel 2: upholds Canada’s revised TRQ rules (Canada win)

|

|

2023

|

CPTPP Panel: NZ wins case vs Canada’s dairy TRQs (violate CPTPP)

|

Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA, 1989)

Historical Context of CUSFTA: The Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1988 by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and President Ronald Reagan as a bold step toward bilateral free trade. It aimed to eliminate tariffs and reduce barriers, placing Canada and the U.S. at the forefront of trade liberalization amid growing global competition. CUSFTA came into force January 1, 1989, creating what was then the world’s largest bilateral free trade area. However, the agreement reflected political compromises. Canada’s supply-managed agricultural sectors – notably dairy and poultry – were largely exempted from liberalization to protect Canadian farmers. As a result, dairy was effectively kept “off the table” under CUSFTA, meaning Canada maintained its existing import quotas and high tariffs on dairy products.

CUSFTA Policy Provisions for Dairy: While CUSFTA dramatically lowered tariffs on most goods, it preserved Canada’s supply management system in dairy. This meant Canada continued to impose strict import quotas on dairy, with prohibitive over-quota tariffs (often well above 100%) to prevent foreign dairy inflows. The U.S., in turn, kept its own import restrictions on certain dairy products (though the U.S. dairy market was generally more open). In practical terms, CUSFTA did not significantly increase U.S.-Canada dairy market access in either direction; it essentially grandfathered in the status quo of limited bilateral dairy trade. The focus of CUSFTA’s agricultural provisions was instead on other commodities where barriers were reduced.

Economic Outcomes of CUSFTA: Given dairy’s exclusion, CUSFTA’s direct impact on dairy trade flows was minimal. Throughout the early 1990s, Canadian dairy imports remained constrained by quota limits, and Canadian dairy exports were negligible due to domestic demand matching supply and export constraints. The agreement’s broader success in boosting bilateral trade did not extend to dairy, which remained a highly protected and regulated sector on the Canadian side. One indirect effect was the increased political salience of dairy: Canada’s preservation of its dairy protections under CUSFTA reaffirmed the government’s commitment to supply management, setting the stage for future trade negotiations where the U.S. would press for dairy concessions.

Successes and Failures of CUSFTA: In terms of dairy, CUSFTA can be seen as a political success but an economic status quo. It succeeded in removing dairy as a point of contention during negotiations – thus ensuring the overall FTA could be concluded – and maintained stability for Canadian dairy farmers. However, it failed to open any new dairy market access. Consumers in Canada saw little benefit in terms of price competition, and U.S. dairy exporters remained locked out. This mutual decision to avoid dairy liberalization averted bilateral dispute at the time, but essentially kicked the can down the road. The exclusion of dairy would later be viewed as a missed opportunity for liberalization, and the issue resurfaced prominently in subsequent agreements.

U.S.-Canada Dairy Trade Timeline (1940s–Present)

- 1947 – GATT Established

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) creates a framework for post-war trade. Agriculture is largely exempt in early GATT rounds, allowing countries to use import quotas to protect sensitive sectors like dairy. Canada maintained import quotas on dairy under GATT Article XI, and the U.S. used Section 22 quotas to restrict dairy imports - 1966 – Creation of Canadian Dairy Commission

Canada establishes the Canadian Dairy Commission (CDC) to support dairy farmers. The CDC sets national support prices for butter and skim milk powder and helps manage surplus removal, laying the groundwork for a supply management system to stabilize prices and farmer incomes. - 1972 – Canada Implements Supply Management

The Farm Products Agencies Act of 1972 authorizes a national supply management system for dairy. By the early 1980s all provinces joined the National Milk Marketing Plan, which fixes provincial milk production quotas (Market Sharing Quotas) to meet domestic demand. Under supply management, Canadian dairy production is controlled, prices are administered, and imports are tightly limited by quotas and high tariffs to protect the domestic market. - 1989 – Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA)

CUSFTA enters into force, phasing out tariffs on many goods between the U.S. and Canada. However, Canada’s supply-managed dairy (along with poultry and eggs) is exempted – Canada retains its import quotas and high tariffs on dairy, and the U.S. keeps its own import restrictions. In other words, CUSFTA’s free-trade provisions did not apply to dairy, leaving pre-existing protections in place. - 1994 – North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

NAFTA (which adds Mexico) comes into effect, but like CUSFTA, it excludes Canada’s dairy sector from tariff elimination. Canada insists on preserving its supply management system in NAFTA, so high dairy tariffs and quotas remain unchanged. U.S.-Canada dairy trade continues to be governed by quotas established under earlier GATT rules. - 1995 – WTO Agreement on Agriculture

The World Trade Organization is created, and members (including U.S. and Canada) sign the Agreement on Agriculture. This requires converting existing agricultural import quotas into tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) with finite low-tariff volumes. Canada converts its dairy quotas to TRQs but sets prohibitive over-quota tariffs (often 200–300% or higher) to ensure imports remain tightly capped. For example, over-quota tariffs on Canadian dairy products range up to ~300%, effectively preserving the protective barrier for Canada’s dairy industry. The U.S. likewise converts its Section 22 dairy quotas to TRQs. Both countries also commit to limits on export subsidies, impacting how they manage dairy surpluses. - 1997 – WTO Dairy Dispute Launched

The U.S. and New Zealand challenge Canadian dairy practices at the WTO. They object to Canada’s “Special Milk Classes” scheme – a pricing system that sold surplus milk to exporters at discounted prices, effectively an export subsidy. In October 1997 the U.S. requests consultations, alleging Canada’s dairy export pricing violates WTO rules (GATT and the Agreement on Agriculture). - 1999 – WTO Ruling on Dairy Export Subsidies

A WTO panel and the Appellate Body rule that aspects of Canada’s special milk class system constitute an illegal export subsidy. Canada is found to have provided milk to processors for export at artificially low prices, exceeding its permitted subsidized export volumes. The WTO decision forces Canada to alter its dairy pricing. Canada eliminates the offending special class pricing for exports (Class 5(d) and (e)), although some compliance wrangling continues in subsequent years. - 2003 – WTO Dispute Settlement

Canada, the U.S., and New Zealand reach a mutually agreed solution to conclude the dairy dispute. Canada agrees to comply with the WTO ruling by ending its special export milk classes and limiting dairy exports to its agreed WTO quota levels (essentially ceasing export subsidies for dairy). This resolution reinforces Canada’s focus on supplying its domestic market and avoiding dumping surplus dairy on world markets. - 2017 – Introduction of Class 7 Pricing

Facing a glut of skim milk byproducts (from rising domestic milk production for butter), Canada overhauls its milk ingredient pricing. In April 2016 Ontario created a new “Class 6” milk price for ingredients, and in February 2017 Canada rolled out a nationwide Class 7 pricing class. Class 7 set ultra-low prices for skim milk components like milk protein concentrate (MPC) and skim milk powder, pegged to world market prices, to discourage imports and allow Canadian processors to use cheap domestic ingredients. This effectively curtailed U.S. ultra-filtered milk exports (which had been entering Canada tariff-free) and enabled Canada to export surplus skim milk powder competitively. The U.S. dairy industry decried Class 7 as a backdoor trade barrier and subsidy, making it a major flashpoint in subsequent trade negotiations. - 2017 – CETA Boosts EU Cheese Access

In September 2017, the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) is provisionally applied. Canada grants significant new duty-free access for European dairy, including an additional 18,500 tonnes of cheese import quota phased in over 5 years. This roughly doubles the EU’s access to the Canadian cheese market, allowing more European fine cheeses to enter before facing tariffs. Canadian dairy farmers protest the loss of market share, while the government provides compensation for the sector. The CETA cheese TRQ is split between Canadian importers and producers, which later becomes a point of contention with the EU. CETA marks the first crack in Canada’s long-held wall protecting dairy, foreshadowing further market access concessions in later deals. - 2018 – CP TPP Trade Agreement

After the U.S. withdraws from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the remaining 11 countries (including Canada) sign the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TPP (CPTPP) in March 2018. Under CPTPP, Canada agrees to new dairy TRQs granting members like New Zealand and Australia greater access to its market. The total new access is about 3.3% of Canada’s dairy market (by volume) for CPTPP partners. This includes specific quotas for milk, cheese, butter, skim milk powder, etc., phased in over multiple years. The CPTPP dairy concessions are slightly smaller than those Canada gave in USMCA, but still significant. Canada’s administration of these TRQs (who gets to import the quota) will later be challenged by New Zealand (see 2023). - 2018 – NAFTA Renegotiation (USMCA) Concluded

Intense negotiations to update NAFTA wrap up in September 2018 with a new accord: the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Canada makes major dairy concessions to the U.S. in this deal. Notably, Canada agrees to eliminate Class 7 (and the related Class 6) from its milk pricing system and to discipline its skim milk powder exports. Additionally, Canada will expand dairy market access for U.S. producers via new TRQs. Once fully phased in, U.S. dairy exports will be allowed tariff-free up to about 3.6% of Canada’s market (annual dairy consumption). These TRQs cover milk, cheese, cream, butter, yogurt, powders, and other products, growing yearly for about 6 years. While Canadian dairy remained protected by supply management, USMCA pried open a bit more access for U.S. farmers – a win for the U.S. dairy industry, though Canadian farmers braced for more competition. - July 2020 – USMCA Takes Effect

The USMCA implementation begins on July 1, 2020. As agreed, Canada eliminates the Class 7 pricing scheme within 6 months of entry, reverting to a more transparent pricing formula for dairy ingredients and committing to monitor and report exports of milk powders and infant formula. Canada also begins allocating the new U.S. dairy import TRQs. These quotas start at smaller volumes and grow each year; once fully phased in, they equate to roughly $70 million in additional U.S. dairy exports (approximately 3.6% of the Canadian dairy market). Tariffs still apply to any U.S. dairy exports above the quota amounts (with over-quota rates still in the 200%+ range). USMCA’s dairy provisions also require Canada to publish more data on its dairy pricing and TRQ usage, increasing transparency. - 2022 – USMCA Dairy Dispute (First Panel)

Despite the new quotas, U.S. officials quickly grew frustrated with how Canada administered the dairy TRQs. Canada was allocating up to 85–100% of certain quotas to domestic processors (Canadian dairy companies), effectively limiting opportunities for U.S. exporters to sell directly to Canadian retailers. The U.S. launched a USMCA dispute in 2021, and in January 2022 a USMCA panel ruled in favor of the U.S., finding that Canada’s allocation of dairy quotas (specifically the large processor-reserved shares) violated the USMCA deal. Canada was directed to change its practices. In response, Canada adjusted its TRQ allocation rules by removing the exclusive processor category – but it introduced new conditions (like a requirement that importers be active in the dairy sector) that the U.S. viewed as still unfair. - 2023 – Second USMCA Panel on Dairy TRQs

The U.S. was unsatisfied with Canada’s revised quota allocation and triggered a second USMCA dispute panel in 2023. This time, the outcome favored Canada. In a November 2023 ruling, the panel sided with Canada, deciding that Canada’s new administration of dairy TRQs was compliant with USMCA rules, even if it continued to frustrate U.S. exporters. Essentially, Canada found ways to meet the letter of its USMCA commitments while still channeling much of the quota to domestic firms. U.S. dairy groups and lawmakers expressed disappointment, arguing that Canada’s approach “harms U.S. dairy producers and processors”. The two USMCA disputes highlight ongoing tensions over the effectiveness of the new market access: the U.S. gained more nominal access on paper, but realizes it must continually enforce the agreement to see tangible results. - 2023 – New Zealand Wins CPTPP Dairy Case

Canada’s dairy import policies faced scrutiny on another front under CPTPP. New Zealand, having secured dairy access under CPTPP, complained that Canada’s TRQ allocations were preventing NZ exporters from utilizing their full quotas (similar to the U.S. complaint). In May 2022, New Zealand launched the first-ever CPTPP dispute, and on September 5, 2023, the CPTPP panel ruled in New Zealand’s favor. The panel found that Canada’s practices (such as reserving quota shares for domestic processors) breached its CPTPP commitments. This ruling puts additional pressure on Canada to liberalize its dairy TRQ administration. Canada accepted the decision and indicated it would work with New Zealand on compliance. The case underscores that Canada’s import controls remain a contentious issue not just with the U.S., but with other trading partners as well.

Detailed Description of Trade Agreements across U.S and Canada

Jump to:

NAFTA | WTO | CETA | CPTPP | USMCA/CUSMA

North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA, 1994)

Historical Context of NAFTA: NAFTA built on CUSFTA by extending free trade to Mexico, coming into force in 1994. Politically, NAFTA’s formation was driven by a desire to integrate North American economies, promote growth, and secure market access, especially between the U.S. and Mexico. Canada joined NAFTA talks to preserve the gains from CUSFTA and avoid being left out of a U.S.–Mexico deal. However, Canada also entered NAFTA determined to uphold its sensitive agricultural policies. The Canadian dairy sector was again explicitly excluded from trade liberalization under NAFTA. Canadian negotiators, backed by a strong domestic consensus, refused to dismantle or substantially alter supply management, considering it essential for farmer stability. Thus, NAFTA’s dairy provisions largely mirrored CUSFTA’s outcome for the U.S.-Canada pair, while opening U.S.-Mexico dairy trade.

NAFTA Policy Provisions for Dairy: Under NAFTA, Canada maintained its steep dairy tariffs and quotas, and no new access was granted to the U.S. beyond existing WTO commitments. A contemporary analysis noted that “because Canada excluded its dairy sector from NAFTA, provisions would affect dairy trade only between the U.S. and Mexico”. In practice, this meant the U.S.-Canada dairy trade remained governed by supply management rules and WTO minimum access commitments, with over-quota tariffs of 200–300% on dairy products into Canada. Canada continued to limit dairy imports to a small percentage of its consumption, and NAFTA did not change those limits. Meanwhile, NAFTA did establish tariff-free dairy trade between the U.S. and Mexico over transition periods, demonstrating how dairy could be liberalized outside the Canadian context.

Economic Outcomes of NAFTA: Between the U.S. and Canada, NAFTA’s implementation saw little change in dairy trade flows, as intended. U.S. dairy exports to Canada continued under the quota-constrained system. Canada’s dairy imports from the U.S. were essentially capped at the tariff-rate quota (TRQ) volumes committed under earlier General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and WTO arrangements (for example, a fixed volume of cheese and butter could enter at low tariff). Above those volumes, punitive tariffs (often ~250%) remained effectively prohibitive. As a result, Canadian consumers and processors did not experience a significant increase in U.S. dairy products under NAFTA. On the other hand, the U.S. dairy industry benefited greatly from NAFTA’s opening of Mexico (U.S. dairy exports to Mexico quintupled in the NAFTA era), but those gains highlighted the stagnation of U.S.-Canada dairy trade. By the late 1990s, Canada’s share of U.S. dairy exports was small relative to Mexico’s, reflecting the closed Canadian market. U.S. frustration grew as global dairy prices fell and Canada’s high internal prices and import barriers persisted.

Successes and Failures of NAFTA: NAFTA can be viewed as a continued failure to address U.S.-Canada dairy barriers, even as it succeeded in broader agricultural trade. The agreement’s success was that it preserved harmonious Canada-U.S. relations by avoiding a politically explosive confrontation over dairy. Canadian dairy farmers continued to enjoy stable prices and production quotas, insulated from foreign competition. However, NAFTA’s failure was that it left a major trade distortion in place: the Canadian dairy market remained largely off-limits, an outcome increasingly criticized by U.S. officials and industry. This incomplete liberalization was explicitly noted by U.S. stakeholders – “when first negotiated, dairy market access to Canada was largely left out…Canada relies on import quotas with severe over-quota tariff rates…without NAFTA renegotiation, U.S. dairy will continue to be saddled with prohibitive tariffs of 200% to over 300%”. Thus, by the 2010s, pressure mounted to revisit dairy in any NAFTA update.

Trade Disputes Under NAFTA: Because NAFTA granted no new dairy rights between the U.S. and Canada, there were few direct NAFTA-based disputes in this area. However, discontent brewed beneath the surface. In the mid-1990s, as the WTO came into force, the U.S. and New Zealand turned to the WTO dispute settlement (rather than NAFTA) to challenge aspects of Canada’s dairy policy, leading to major cases (discussed under WTO section). NAFTA’s own dispute resolution mechanism was never used to challenge Canadian dairy protections, since these were explicitly permitted by the agreement. Still, NAFTA’s legacy was a sense that its state-to-state dispute process was “chronically deadlocked” and ineffective in some areas. This would later influence the design of USMCA’s enforcement tools for dairy.

World Trade Organization (WTO) and Dairy Trade Rules

Historical Context of WTO: The WTO’s establishment in 1995, via the Uruguay Round, marked the first significant multilateral discipline on agricultural trade. Both the U.S. and Canada joined the WTO and agreed to the new Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). For dairy, this introduced important constraints: countries had to convert import quotas into tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) and commit to minimum market access, as well as curb export subsidies. The political impetus was to gradually liberalize farm trade globally, though countries like Canada fought hard to retain their core policies. Canada’s WTO commitments on dairy reflected a defensive stance – high tariff “walls” replaced outright import bans, and minimum import quantities were set just enough to satisfy requirements. The U.S., as a competitive dairy exporter, generally pushed for more open markets, but it also maintained some dairy support policies within WTO limits.

WTO Policy Provisions Affecting Dairy: Under the WTO AoA, Canada listed specific TRQs for dairy products (e.g. roughly 64,500 metric tons for fluid milk and smaller TRQs for cheese, butter, etc.), with over-quota tariffs often around 200–300%. These TRQs ensured at least a small fraction of Canadian dairy consumption came from imports at a low tariff (often allocated to historical importers). The U.S. likewise established TRQs for certain dairy imports (though U.S. tariffs on most dairy categories were much lower than Canada’s). Crucially, the WTO outlawed certain types of export subsidies. In the late 1990s, the U.S. and New Zealand challenged Canada’s practice of selling lower-priced milk to exporters (the “special milk classes” or later the “Commercial Export Milk” scheme) as an implicit export subsidy. In 2002, the WTO Appellate Body ruled that Canada had indeed breached its WTO obligations by providing export subsidies to its dairy industry, allowing it to export dairy products beyond its subsidy limits. As a result, Canada was forced to dismantle its special export milk program and accept tight limits on dairy exports. This effectively capped Canada’s presence in international dairy markets and reaffirmed that its high domestic prices could not be used to cross-subsidize exports.

Economic Impacts of WTO: WTO rules somewhat opened Canada’s dairy market at the margins. For example, the required TRQs allowed limited quantities of foreign cheese, butter, milk powder and other products into Canada at low tariff rates. The U.S. (as well as the EU and others) thus gained small, guaranteed footholds in the Canadian market through WTO commitments. However, the volumes were modest (often on the order of a few thousand tons per product), so the overall trade flow impact was limited. Canadian dairy prices remained well above world levels, indicating that supply management’s protective effect endured. One notable development was growth in niche cross-border trade not anticipated by old quotas – for instance, U.S. exports of ultra-filtered milk (a high-protein liquid milk concentrate) to Canadian cheese processors grew in the 2000s because this product was not explicitly listed in Canada’s WTO schedule and thus entered tariff-free. By the mid-2010s, U.S. ultra-filtered milk exports to Canada reached about $150 million annually. This revealed how market forces sought cracks in the system, exploiting undefined categories.

On export discipline, the WTO case outcome meant Canada could only export dairy within strict limits (essentially no significant exportable surplus was allowed unless sold at world price without subsidy). Canadian dairy farmers consequently focused entirely on the domestic market. The WTO also required all members to notify and reduce certain domestic support measures over time. Canada categorized its supply management price support as WTO-legal (within “Aggregate Measurement of Support” limits) while the U.S. reduced its old price support programs and shifted to less trade-distorting support. Neither country’s overall dairy policy was dismantled by the WTO, but the framework of global rules set the stage for later bilateral tensions. The WTO Doha Round (launched in 2001) sought further agricultural trade reforms. By 2004, however, Canada’s defensive position on supply management left it isolated – “it was one against 146” countries at the WTO talks, as Canada resisted pressure to concede more on dairy. The Doha Round ultimately stalled, meaning no new multilateral dairy trade liberalization occurred after the initial Uruguay Round gains.

Legal Disputes and Enforcement of WTO: The WTO has been the arena for the most significant legal disputes on U.S.-Canada dairy trade. The early 2000s “Canada – Dairy” cases (DS103/113) were landmark rulings that clarified the limits of Canada’s supply management under trade law. After Canada lost those cases and ended its export subsidy-like programs, its ability to intervene in global dairy pricing was curtailed. More recently, when new disagreements emerged (such as Canada’s creation of a low-priced milk ingredient class – Class 7 – in 2017), the U.S. again considered WTO action, though this was overtaken by USMCA negotiations. Notably, other WTO members have also kept pressure on Canada: in 2022, New Zealand launched a WTO complaint about Canada’s dairy TRQ allocation under CPTPP, parallel to U.S. concerns. (In 2023, New Zealand instead won a CPTPP panel on this issue, discussed below.) Overall, WTO rules provided a baseline of commitments (like TRQ minimums and subsidy prohibitions) and a forum to enforce them, significantly shaping Canada’s dairy trade policy even as supply management remained largely intact domestically.

Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA, 2017)

Historical Context of CETA: CETA is a free trade agreement between Canada and the European Union, provisionally applied in 2017. Its formation was motivated by both economic and strategic factors: Canada sought to diversify trade beyond the U.S. (especially after years of heavy reliance on NAFTA), and the EU aimed to secure better access to the North American market ahead of other competitors. For Canada, CETA negotiations under the Harper government meant balancing offensive interests (like gaining EU market access for Canadian goods such as beef and machinery) with defensive interests (protecting sensitive sectors like dairy). The EU is a major dairy exporter (notably of cheese), so dairy market access became a key EU demand. Politically, Canada agreed to some dairy concessions to clinch the deal, while assuring farmers that supply management was still being preserved in essence. CETA thus marked the first time Canada granted a substantial dairy market opening in a trade agreement, albeit to Europe rather than the U.S., which raised concerns for Canadian dairy producers.

CETA Policy Provisions for Dairy: Under CETA, Canada opened new Tariff-Rate Quotas for EU dairy, especially cheese. The agreement granted the EU an additional quota of 17,700 metric tons of cheese (16,000 tons of “high-quality” cheese and 1,700 tons of industrial cheese) to be imported tariff-free, phased in over several years. This volume was significant, roughly doubling Canada’s previous WTO cheese import commitment. The new cheese TRQ amounted to about 2% of Canada’s cheese market, which is approximately 1.3% of Canada’s total dairy market by milk solids. Apart from cheese, smaller CETA TRQs were established for other EU dairy products (such as milk powders or butter), though cheese was the headline item. Notably, Canada maintained very high tariffs on dairy products outside these quotas (e.g. over 200% on many items), so CETA’s effect was limited to the quota amounts. The agreement did not dismantle supply management; it merely carved out additional import access. Canada also retained the right to allocate import licenses for these TRQs as it saw fit. In practice, the government split the cheese quota between Canadian importers (including retailers and food distributors) and domestic dairy processors. This allocation approach became contentious – dairy processors argued they should receive the majority of licenses to offset losses, whereas giving a share to non-dairy importers meant more competition for domestic cheese producers.

Economic Impacts of CETA: CETA’s implementation brought a notable increase in European cheese imports to Canada, gradually as the quota expanded. European cheesemakers gained lucrative new shelf space in Canadian grocery stores. For Canadian consumers, this meant greater availability of specialty and artisanal cheeses, potentially at slightly lower prices due to duty-free entry for those volumes. Canadian dairy farmers and processors, however, viewed this as a loss of market share. The Dairy Processors Association of Canada projected about $670 million in lost market share or reduced returns over time due to the influx of EU cheese. In terms of overall dairy farm revenue, CETA’s cheese quota represented a small reduction (roughly 1% or so of domestic production displaced), but it was concentrated in the cheese segment. Canadian cheese makers faced stiffer competition, especially for premium cheese sales. The government acknowledged these impacts by offering compensation. Shortly after CETA, Canada announced a multiyear compensation package for the supply-managed sectors; for dairy farmers, this included direct payments totaling $1.75 billion (Canadian dollars) over eight years to offset income losses from CETA and the later CPTPP deal. The EU’s benefit was clear in export data – EU cheese exports to Canada jumped, while Canadian dairy exports to the EU remained negligible (Canada wasn’t expected to export dairy, given higher costs and export caps). Thus, economically, CETA was a one-sided gain for the EU dairy industry.

Successes and Failures of CETA: From a trade policy perspective, CETA was a success in that it demonstrated Canada’s willingness to make calibrated concessions in supply management to achieve broader trade goals. It diversified Canada’s trade partnerships and was hailed as a “gold-standard” agreement. However, in the dairy realm, it was met with significant criticism domestically. Canadian dairy stakeholders saw it as a failure to defend the integrity of supply management, since it opened the door, albeit slightly, to foreign dairy. The allocation of cheese import licenses in CETA was also controversial – when more than half the quota was awarded to distributors not tied to Canadian processors, processors argued that it “gave away” the value of their prior investments. This internal dispute underscored that even a small market access concession can have distributional consequences. There were no formal trade disputes between Canada and the EU over dairy under CETA (the EU got what it wanted, and Canada complied with implementation), so in that sense it was smoothly executed. The “failure” if any was political: it weakened the once iron-clad policy of no dairy market openings. This precedent would carry into subsequent negotiations like CPTPP and USMCA, cumulatively eroding the policy that Canadian politicians had long promised to defend.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, 2018)

Historical Context of CPTPP: The CPTPP is a multilateral trade agreement among 11 Pacific Rim countries, including Canada (but notably not the United States, which withdrew from the original Trans-Pacific Partnership). Concluded in 2018, CPTPP was driven by the desire of these countries to enhance trade ties in the Asia-Pacific and set high-standard trade rules. Canada joined the TPP negotiations in 2012, again facing pressure to open its protected agricultural sectors. When the U.S. was part of the talks, it pushed hard for Canadian dairy liberalization, and Canada reluctantly agreed to some concessions in the tentative 2015 TPP deal. After the U.S. exit in 2017, the remaining countries carried on with CPTPP, largely retaining those market access concessions (even though the U.S. was no longer around to benefit from them). For Canada, this meant that CPTPP would open its dairy market to Australia, New Zealand, and other Pacific exporters. Politically, this was sensitive – New Zealand, in particular, as a world-leading dairy exporter, coveted access to Canada. Canada’s calculus was that the overall agreement (opening markets in Asia for Canadian industries) justified the difficult concessions in dairy. The Trudeau government also paired CPTPP ratification with promises of compensation to dairy farmers. Thus, CPTPP became another step in slowly chipping away at Canada’s dairy protection, without dismantling it outright.

CPTPP Policy Provisions for Dairy: Under CPTPP, Canada agreed to provide the partner countries with new dairy TRQs totaling about 3.25% of its domestic dairy market. This 3.25% market share was spread across various dairy categories – including fluid milk, cream, cheese, skim milk powder, butter, and others – with phased-in quota volumes. For example, CPTPP established a new import quota for milk starting at 8,333 metric tons in year 1 (2018/19) and rising to over 50,000 MT by year 6, which by then equates to roughly 3.25% of Canada’s fluid milk consumption. Similar quotas were set for butter, cheese, milk powders, yogurt, and ice cream. All CPTPP countries (like New Zealand, Australia, etc.) share these quotas on a first-come, first-served basis, and imports within the quotas enter tariff-free. As with CETA, over-quota tariffs remain in place (often exceeding 200%), so the quotas define the extent of market opening. Additionally, CPTPP contains rules to ensure quota administration is transparent. Canada retained discretion in how to allocate these TRQs among importers. It decided to give the bulk of CPTPP dairy import licenses to Canadian dairy processors (up to 85% in categories like fluid milk and cream) so that processors could import inputs for further processing or share in the import profits. This was intended to mitigate harm by letting domestic firms capture some value from the quota rents.

Economic Impacts of CPTPP: The CPTPP dairy concessions, once fully implemented, represent a larger import surge than CETA’s. Dairy Farmers of Canada estimated that CPTPP would reduce the domestic market available to Canadian producers by 3.25% (a loss they equated to about 8% of farm revenues when combined with CETA and USMCA concessions). In concrete terms, Canada will be importing tens of thousands of additional tons of dairy products annually. However, the actual impact depends on whether foreign exporters fully utilize the quotas. For certain categories like fluid milk and cream, logistical challenges (perishability, shipping costs) may limit usage. Indeed, Canada’s official analysis projected that CPTPP dairy import quotas for liquid milk might remain under-filled due to the economics of shipping milk across oceans.

Conversely, imports of storable products like butter, cheese, and milk powder from New Zealand or Australia are expected to increase markedly, as those countries are efficient producers. Canadian consumers could see modest benefits: more variety in butter and cheese, and possibly slight price relief if import competition increases. The greater effect, though, is on Canadian dairy farmers’ production quotas, which may be scaled back by the supply management system to accommodate the increased imports (since Canada’s demand is essentially filled first by domestic quota and then by mandated imports). This means forgone production opportunities for Canadian farms, translating to reduced farm revenue. The Canadian government acknowledged this; in addition to the $1.75 billion farmer compensation (covering CETA and CPTPP), it also set up an investment fund for dairy processors to the tune of $100-150 million to help them modernize and stay competitive. On the export side, CPTPP gave Canada some new access to other markets, but Canada’s dairy exports are minimal due to its high costs and export limits. Global Affairs Canada estimated CPTPP would increase Canadian dairy imports by 13% but boost Canadian dairy exports by only 0.5%, a net negative for the sector. Thus, economically, CPTPP’s dairy provisions largely benefit foreign exporters (especially New Zealand, which secured meaningful new quotas) while challenging the Canadian dairy industry to adapt to a slowly liberalizing environment.

Successes and Failures of CPTPP: CPTPP’s dairy outcome can be seen as a success of international negotiation but a point of controversy at home. It succeeded in balancing interests among 11 countries – Canada’s concession of 3.25% was enough to satisfy partners like NZ and Australia, enabling the broader deal. It also showed Canada’s trading partners that even a sacred cow like supply management could be negotiated within limits. However, from the perspective of Canadian dairy farmers, this was another erosion of their protected market, viewed as a failure by the government to fully uphold previous promises of no further market access. This eroded trust, prompting the government to promise that CPTPP was a one-time sacrifice. In implementation, one contentious issue has been how Canada administers the quotas. By allocating a large share to domestic processors, Canada aimed to blunt the competitive impact. Yet, this practice was challenged by New Zealand, which argued it violated the spirit of the agreement by discouraging full utilization of quotas. In 2023, a CPTPP dispute settlement panel ruled in New Zealand’s favor, finding that Canada’s dairy quota administration was not consistent with CPTPP obligations. Essentially, Canada was told it must make the quota allocation more importer-neutral to allow foreign dairy easier entry. This outcome is a reminder that even when agreements are signed, how they are executed can lead to disputes. In terms of broader success, CPTPP did not lead to any immediate collapse of Canadian dairy – the industry remains robust but under pressure. One could say CPTPP was a managed compromise: it failed to satisfy hardliners on either side (it’s not free dairy trade, but also not zero change), yet it achieved a diplomatic win by bringing Canada into a major Pacific pact. Canadian officials tout the deal’s benefits for many sectors, implicitly framing the dairy concession as a reasonable price for those gains.

United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA/CUSMA, 2020)

Historical Context of USMCA/CUSMA: The USMCA is the successor to NAFTA, entering into force in July 2020. Its negotiation was driven by the U.S. Trump administration’s demand to update NAFTA and address perceived imbalances. Dairy was a top U.S. priority in the renegotiation, as American dairy groups and lawmakers had long been frustrated with Canada’s closed market and new irritants like Class 7 milk pricing. The political context included vocal criticism of Canadian dairy tariffs by U.S. leaders in 2017–2018, which even contributed to trade tensions (President Trump at one point decried Canada’s “270% tariffs” on dairy as “unfair”). Canada, under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, entered the talks aiming to preserve overall tariff-free trade but knew some dairy concessions would likely be unavoidable given U.S. leverage. Indeed, the final USMCA deal saw Canada agree to further open its dairy market to the U.S., alongside concessions in other supply-managed products (poultry, eggs). For Canada, this was among the most difficult pills to swallow politically – after already giving access to the EU and CPTPP countries, now its closest neighbor and biggest dairy trade partner, the U.S., would also get a bigger foothold. USMCA thus represents the culmination of a gradual process of Canada yielding increments of its dairy protection in trade agreements.

USMCA/CUSMA Policy Provisions for Dairy: USMCA’s dairy chapter contains several significant elements: (1) Increased U.S. dairy access via new TRQs, (2) Elimination of Canada’s Class 7 pricing policy, and (3) Export restriction measures. First, Canada agreed to establish TRQs exclusively for U.S. dairy products across 14 categories (including milk, cream, cheese, butter, yogurt, milk powders, and ice cream). In total, these quotas amount to approximately 3.5% of Canada’s dairy market for U.S. producers– effectively matching the scale of access Canada gave in CPTPP, but now reserved for the U.S. market share. The TRQ volumes ramp up over a 6-year implementation period: for example, the fluid milk quota starts at about 8,333 MT in year 1 and doubles by year 2, reaching 50,000 MT by year 6. After year 6, most quotas grow 1% annually for another 13 years. U.S. dairy exports within these quotas enter Canada duty-free, while any exports above the quotas still face Canada’s high WTO tariffs. Secondly, Canada agreed to abolish the Class 6/7 milk pricing scheme within six months of USMCA’s start. Class 7 had allowed Canadian authorities to price surplus skim milk ingredients at low world-market levels, which helped domestic processors and undercut U.S. ultra-filtered milk imports. Under USMCA, milk ingredients were reclassified and a formula tied to U.S. prices was imposed, preventing Canada from undercutting U.S. prices domestically. Moreover, transparency requirements compel Canada to publish data on milk classes and prices.

Thirdly, USMCA introduced limits on Canadian dairy exports of certain products. If Canada’s exports of skim milk powder (SMP) and milk protein concentrate exceed 55,000 tons in year 1 (35,000 in year 2), a punitive surcharge kicks in on additional exports. Similarly, infant formula exports have specific thresholds. These provisions, unprecedented in trade deals, were designed to prevent Canada from dumping excess dairy on global markets to the detriment of U.S. and New Zealand. Additionally, the U.S. reciprocally opened a small aggregate TRQ for Canadian dairy exports into the U.S. (e.g., about 1,750 thousand liters for fluid cream and milk, growing to nearly 12 million liters by year 19) – a token gesture since U.S. market is much larger and already fairly open. In summary, USMCA’s dairy provisions represented a comprehensive approach: market access, policy reform, and export control.

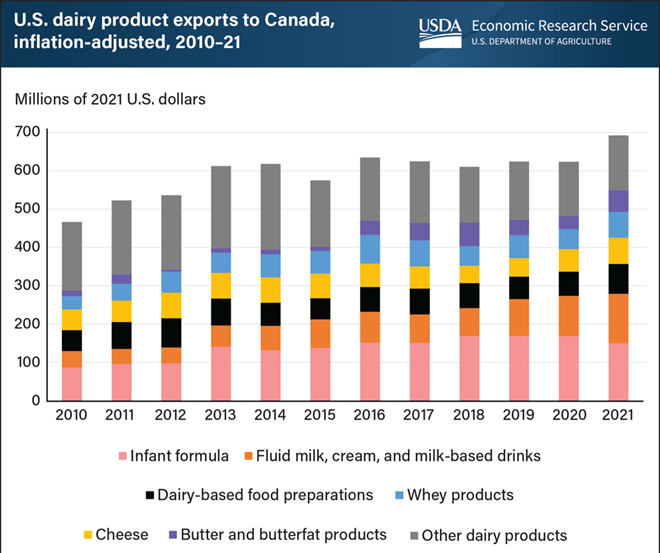

Economic Impacts of USMCA/CUSMA: Early evidence suggests that USMCA has indeed boosted U.S. dairy exports to Canada. After USMCA’s implementation in mid-2020, U.S. dairy exports to Canada increased noticeably. By 2021, U.S. dairy export value to Canada reached about $792 million (nominal), up from around $620 million in 2017. This growth reflects the new quota-enabled sales, particularly of products like milk protein concentrates, cream, and cheese that filled USMCA quotas. The chart below illustrates the rising trend of U.S. dairy exports to Canada over the past decade, showing a clear uptick around 2020–2021 as USMCA came into effect. Notably, infant formula and cream-based products have led the growth, as Canada now imports more of these from the U.S. within the duty-free TRQs. Canadian dairy processors, facing more U.S. competition on high-value products, have expressed concern about lost market share. Dairy Farmers of Canada estimated USMCA would ultimately allow imports equivalent to an additional 0.5% of Canada’s dairy consumption on top of prior trade deals, bringing total foreign share of the market to about 18% (when including WTO, CETA, CPTPP, USMCA combined). For Canadian consumers, USMCA’s impact on retail dairy prices is not yet clearly felt; prices remain higher than in the U.S., partly because the imported volume is still relatively small in proportion. However, specific industries like Canadian cheese makers or milk ingredient suppliers are seeing increased competition, which could constrain their pricing power. From the U.S. perspective, USMCA opened an estimated $200 million in additional dairy exports opportunity. While this is modest relative to the size of the U.S. dairy sector, it can be significant for certain regions (e.g., border states like Wisconsin and New York benefit from selling more fluid milk and specialty products to nearby Canadian markets). Importantly, the elimination of Class 7 removed a market distortion that had been depressing U.S. ultra-filtered milk exports; U.S. exporters have since regained access to Canadian buyers for these protein concentrates. On the Canadian side, one economic adjustment has been increased government outlays for compensation: Canada has announced compensation to dairy farmers for USMCA as well (expected in addition to the CETA/CPTPP $1.75 billion package). In sum, economically, USMCA made incremental but tangible changes: it pried open the Canadian dairy market slightly more, aligned certain Canadian prices with U.S. levels, and curbed Canada’s ability to surplus dump, all of which strengthen U.S. dairy’s competitive position in North America.

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service using data from Foreign Agricultural Service’s Global Agricultural Trade System and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

U.S. dairy product exports to Canada (2010–2021), inflation-adjusted to 2021 dollars. Exports rose from $466 million in 2010 to $691 million in 2021, reflecting increasing U.S. access. Notable categories include infant formula (pink), fluid milk/cream (orange), cheese (yellow), butterfat products (black), whey (blue), and others (grey). The uptick in 2020–21 corresponds with new access under USMCA.

Legal and Trade Disputes of USMCA/CUSMA: USMCA established a modern state-to-state dispute settlement mechanism, which was quickly tested on dairy. The agreement’s text on TRQ administration requires that Canada not allocate quotas in a manner that discourages their use. By 2021, the U.S. alleged that Canada’s method of allocating USMCA dairy quotas – reserving a large percentage for domestic processors – was violating the agreement, as it left some quotas under-filled and limited U.S. exporters’ direct access to import licenses. The U.S. launched the first USMCA dispute panel on this issue. In January 2022, the panel ruled in favor of the United States, finding that Canada’s practice of allocating quota exclusively to processors was inconsistent with Canada’s commitments. Canada accepted the ruling and adjusted its allocation policy, e.g. opening a portion of quotas to non-processors. However, the U.S. was still unsatisfied with the new allocation method and brought a second complaint in 2022. In a November 2023 panel decision, Canada prevailed, as the panel found Canada’s revised measures were now in compliance. These back-to-back cases demonstrate both the functionality and the limitations of USMCA enforcement. Unlike NAFTA’s often-deadlocked system, the USMCA panels operated efficiently and delivered binding decisions. This is cited as a success for dispute resolution, proving that trade irritants can be resolved through the agreement’s framework rather than escalating into trade wars. On the other hand, the mixed outcomes (one win for the U.S., one for Canada) indicate that much depends on legal interpretation of fine print. The U.S. dairy industry continues to argue that Canada’s quota administration remains “manipulative,” while Canada insists it is honoring the letter of the deal. Outside of USMCA’s own panels, the agreement’s provisions to eliminate Class 7 averted a potential WTO case the U.S. had considered. So far, no WTO disputes have been filed between the U.S. and Canada on dairy since USMCA, suggesting the focus has shifted to USMCA’s internal enforcement. USMCA also includes a review clause after six years for the dairy provisions, meaning the two sides will revisit the dairy terms in 2025–2026 to assess if any adjustments are needed, providing an institutional check-in on this often contentious trade file.

Successes and Failures of USMCA/CUSMA: USMCA’s dairy chapter is often cited as a successful negotiation for the U.S. and a managed compromise for Canada. For the U.S., it achieved longstanding objectives: new market access (3.5% of Canada’s market valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars) and the removal of an unfair pricing scheme. U.S. officials and dairy groups viewed this as a win for fairness and for farmers, even though the absolute size of the gain is small relative to the U.S. industry (3.5% of Canada’s market is only a fraction of U.S. annual milk production). The U.S. demonstrated that persistent trade diplomacy could pry open even a well-defended sector. For Canada, the success was in ending NAFTA uncertainty and avoiding much harsher outcomes. Canada retained the core of supply management; 96.5% of its dairy market remains supplied by domestic producers under controlled prices. By agreeing to relatively limited concessions and then following the dispute panel rulings, Canada navigated the storm. The federal government’s ability to placate farmers with compensation also helped frame USMCA as acceptable. In terms of failures, one could argue USMCA failed to fully settle the dairy tension – disputes arose almost immediately, indicating lingering differences in interpretation and interest. U.S. exporters still face complexities getting their products to Canadian consumers, and Canadian farmers still feel exposed and have had to rely on government payouts. Some critics on the U.S. side say that ~3.5% access is “financially negligible” in the grand scheme (though symbolically important), and that U.S. negotiators could have pushed for more. On the Canadian side, critics lament the loss of Class 7, as it has slightly raised input costs for Canadian processors (they now must pay more competitive prices for skim components) and removed a tool Canada had to deal with surplus milk. Another failure might be consumer impact – despite multiple agreements, Canadian retail dairy prices remain high, so from a consumer welfare perspective, the benefits of these trade deals have not significantly materialized in cheaper milk or cheese at the grocery store. Lastly, the fact that enforcement required multiple panel cases could be seen as a failure of smooth implementation, though ultimately the mechanisms worked as designed.

Comparative Economic Analysis of Dairy Trade under These Agreements

Trade Flows

Over the past three decades, U.S.-Canada dairy trade has grown in absolute terms, but this growth has been constrained by policy limits. The U.S. consistently runs a dairy trade surplus with Canada – Canada is a top-3 export market for U.S. dairy (second only to Mexico in recent years). U.S. dairy exports to Canada climbed from about $450 million in 2010 to $690 million in 2021 (inflation-adjusted), roughly a 48% increase. This trend accelerated after 2017 as new access from CETA, CPTPP, and USMCA began to take effect. Key exported products include infant formula, cream and fluid milk, cheese, yogurt, and butterfat products. On the import side, the U.S. imports very little dairy from Canada – typically specialty items and some cheese – generally under $100 million annually, since U.S. markets are well-supplied domestically and Canadian prices are high. Thus, Canada’s role is primarily that of an import market in dairy, not an exporter. Each successive trade agreement nudged the dial toward more U.S. dairy presence in Canada: WTO rules ensured a baseline of access (e.g., the U.S. filling a significant portion of Canada’s WTO-mandated cheese import quota); CETA granted EU suppliers additional shares (squeezing some U.S. share in cheese, potentially); CPTPP allowed Oceania suppliers a crack at the market; and USMCA carved out specific, potentially larger quotas for the U.S. alone. The net effect has been that foreign dairy imports now account for a growing, though still small, percentage of Canada’s consumption – currently estimated around 10% and projected to rise toward 18% when all agreements are fully phased in. This is up from perhaps 5% or less before 2017.

In terms of specific impacts: cheese imports have grown via EU and U.S. quotas, milk protein substances (like MPC and infant formula bases) have increased from the U.S., and butter imports from New Zealand and the U.S. have ticked up (especially in times of domestic shortfall or high world stock). The quantitative impact on trade flows can also be seen in utilization rates of TRQs. Canadian data show that many of the import quotas are now being filled at high rates, reflecting demand for foreign dairy. For example, in 2021, Canada’s import quota fill rate for butter was over 90%, and for cheese around 80% (combining WTO, CETA, CPTPP quotas). Some TRQs (like fluid milk under CPTPP) saw low fill rates early on due to logistical reasons, but U.S. fluid milk under USMCA has been filling as it can be trucked across the border. Overall, these agreements have cumulatively increased the volume of dairy trade. Still, relative to the size of the U.S. and Canadian dairy sectors, the changes are moderate. The U.S. produces over 100 billion liters of milk per year; gaining access to a few hundred million liters equivalent in Canada is beneficial, but not transformative industry-wide. For Canadian dairies, losing a few percentage points of market share might seem small, but in a zero-sum quota environment it can mean the difference between expansion or cutbacks for farms and processors. Thus, even modest trade flow changes are keenly felt by industry participants.

Dairy Pricing

A core issue has been the price gap between Canadian and world/U.S. dairy prices. Canada’s supply-managed system maintains farm gate milk prices typically well above those in the U.S. or world market. Trade agreements, by introducing some cheaper foreign dairy products into Canada, have the potential to narrow that gap for specific products. In practice, the impact on Canadian consumer prices has been limited so far because import volumes are quota-capped. Within the quotas, importers often capture a rent (the difference between high domestic price and lower import cost), which may or may not be passed to consumers. For instance, European fine cheeses entered Canada duty-free under CETA, but retail prices did not plummet; they likely decreased modestly or consumers saw higher-quality options at similar prices. The presence of foreign competition can restrain extreme price hikes in Canada – e.g., if Canadian butter production falls short and domestic prices rise, the Canadian Dairy Commission may import additional butter within its WTO quota to stabilize the market at the target price. Thus, trade agreements provide a safety valve for Canadian dairy prices, preventing shortages, but they have not fundamentally altered the supply-managed price level yet. On the U.S. side, dairy prices are largely market-driven and volatile; increased exports to Canada can have a mild supportive effect on U.S. milk prices by boosting demand, but given the U.S. market size, the effect is marginal. One notable pricing change was the elimination of Class 7 in Canada: this led to Canadian processors paying more for certain milk components (protein solids) – roughly aligning those prices with U.S. levels. That likely raised ingredient costs for Canadian-made cheese and yogurt slightly, reducing their price advantage from the old system, but also removed the artificially low-priced competition for U.S. ingredient exports.

In summary, while agreements have not equalized U.S. and Canadian dairy prices, they have enforced some convergence (for inputs) and provided consumers a bit more choice. A Canadian shopper can now find more imported dairy items which might be priced somewhat lower than equivalent domestic specialty products, but staples like milk and butter remain priced by Canadian supply management (with imports just supplementing supply).

Profitability and Competitiveness

The gradual opening of Canada’s dairy market has mixed effects on profitability for stakeholders. Canadian dairy farmers have seen their production quotas trimmed slightly to accommodate imports, which can reduce their revenue unless compensated. The government’s financial compensation has so far offset many of these losses, effectively socializing the cost of trade liberalization. Canadian processors face stiffer competition but also, in some cases, gained import licenses (as in CPTPP) that they can use or sell, which offset competitive losses. The end of Class 7 means Canadian processors can’t source ultra-filtered milk at dirt-cheap prices internally, so they might rely more on imports or pay farmers more – this squeezes processor margins unless they become more efficient or innovate products. On the U.S. side, dairy farmers benefit indirectly: more export sales can improve milk prices at the margin, and specific industries (like ultrafiltered milk producers, cheese exporters) see direct revenue gains. U.S. processors and exporters find a new outlet for high-quality products in Canada, supporting their profitability, especially when U.S. milk supplies are abundant. However, the complexity of Canada’s import licensing can add costs or uncertainties for U.S. exporters (e.g., having to partner with Canadian quota holders). Competitiveness-wise, the agreements expose the Canadian dairy sector to a bit more international competition, which can spur efficiency. Canadian farms have been growing in size and productivity over time, partly in anticipation of needing to compete on a slightly more level field. Yet, significant protection remains, so the pace of change is controlled. The U.S. dairy industry, which is highly competitive globally, is well poised to capitalize on any new access – the challenge is usually political, not an issue of capacity.

Market Distortions

Each agreement attempted to reduce market distortions, yet some remain. Supply management itself is a distortion (keeping domestic prices above world levels and restricting supply), and these trade deals only chip away at it. Tariff-rate quotas are inherently second-best solutions – they liberalize trade but also create quota rent distortions and administrative complexities. We see this in how Canada’s TRQ allocations became a battlefield: giving quotas to processors versus retailers alters who gains financially, and when quotas go unfilled, it indicates inefficiencies or barriers in the system beyond pure supply and demand. The USMCA panel highlighted that even when volume restrictions aren’t binding, administration can constrain trade. Another distortion was Class 7, which was effectively eliminated to remove its trade-distorting effect (it had allowed cross-subsidization and import substitution in a non-transparent way). With Class 7 gone, a more level playing field exists for milk ingredients.

One could argue that an enduring distortion post-USMCA is the continued existence of extremely high over-quota tariffs – effectively, trade beyond a certain volume is shut off. This means that normal market signals (like if Canadian prices spike due to a shortage) cannot easily bring in additional imports because outside of the agreed TRQs, tariffs make it non-viable. In an ideal market, price differences would invite arbitrage (imports) until price gaps close; in the managed trade scenario, that arbitrage is strictly limited. Thus, Canadian consumers might still pay more for dairy than they would under free trade, and U.S. producers cannot fully exploit their competitive advantage. The agreements have, however, reduced the potential for blatant unfair practices: for example, with clear export limits in USMCA, Canada cannot dump excess SMP on world markets at subsidized prices, which helps avoid depressing world prices unfairly. In general, each step (WTO, CPTPP, USMCA) has moved the needle towards a more market-oriented regime, but significant distortions remain by design.

Trade Disputes and Enforcement Mechanisms

Throughout this history, trade agreements have been accompanied by legal disputes and enforcement actions, particularly regarding whether Canada’s dairy practices conform to commitments. A few major episodes stand out:

- WTO Dairy Subsidy Disputes (1997–2002): The U.S. and New Zealand challenged Canada’s special milk class system, arguing it was an export subsidy circumventing WTO rules. WTO panels and the Appellate Body ruled against Canada. Enforcement came through WTO authorized sanctions, but Canada chose to comply by ending the offending program in 2003. This set a precedent that Canada’s dairy system was not inviolate – international law could force changes at the margins.

- Ingredient Pricing (Class 7) Dispute: Rather than a formal case, this was a dispute that played out in the court of public opinion and in trade negotiation (USMCA). The U.S. viewed Canada’s 2016 introduction of Class 7 ingredient pricing as a backdoor way to block imports (like ultra-filtered milk) and boost exports, calling it a violation of the spirit of trade commitments. The resolution came via USMCA, with Canada agreeing to end Class 7, effectively settling the dispute in negotiations rather than litigation.

- USMCA TRQ Allocation Disputes (2021–2023): As detailed above, the U.S. twice took Canada to USMCA dispute settlement over how dairy quotas were allocated. The first panel found Canada’s allocation to processors was too restrictive and inconsistent with ensuring the U.S. received the full benefit of its quotas. The second panel found Canada’s revised approach acceptable. USMCA’s mechanism proved its worth by delivering binding rulings within a set timetable, showing a clear improvement over NAFTA’s often stalled system. The enforcement mechanism in USMCA (Chapter 31 dispute panels) thus far has worked to clarify rules and ensure compliance. Both the U.S. and Canada have respected the outcomes, underlining confidence in the system.

- CPTPP Dispute (New Zealand v. Canada, 2022–2023): In parallel with the USMCA issue, New Zealand, not having a bilateral mechanism, utilized CPTPP’s dispute process against Canada for similar complaints about TRQ administration. In September 2023, the CPTPP panel ruled in New Zealand’s favor, finding Canada’s dairy quota allocation breached CPTPP requirements. This reinforces that Canada’s management of quotas is under scrutiny multilaterally, and it must adjust practices across the board. The CPTPP enforcement mechanism here demonstrated that even without U.S. involvement, other trading partners can successfully challenge Canada’s implementation.

- Other Disputes: There have been a few smaller trade spats and rhetoric exchanges. For example, during a 2018 tariff war (unrelated to dairy agreements), the U.S. imposed steel tariffs and Canada retaliated with tariffs on various U.S. goods including yogurt and certain dairy products, purely for political pressure. Those were temporary and resolved with the removal of steel tariffs in 2019. Additionally, Canada has occasionally questioned U.S. dairy support programs (like export credits or state-level pricing classes) at the WTO, but no major cases materialized from the Canadian side. Both countries typically comply with WTO notification requirements for dairy subsidies, and if anything, Canada filed a WTO case in 2018 against U.S. dairy and other farm subsidies as a broader strategic move, though it did not progress far.

In terms of enforcement mechanisms: we have the WTO’s dispute settlement (which until recently had a functioning Appellate Body, now stalled but the disputes mentioned occurred earlier), and the regional mechanisms in NAFTA (Chapter 20) and USMCA (reinforced Chapter 31). NAFTA’s Chapter 20 panels were seldom used; in dairy, they weren’t used at all because there were no obligations to enforce. USMCA’s equivalent has already been used, indicating a more proactive enforcement culture under the new agreement. Also, USMCA provides for monitoring – Canada must report on dairy exports monthly and be transparent about its pricing, giving the U.S. data to watch for violations. If either party believes there is a breach (e.g., if Canada reintroduced something like Class 7 under another name), they can call for consultations or panel review. The existence of snap-back tariffs or withdrawal threats was also looming – the U.S. made it clear it could always resort to other trade actions if disputes weren’t resolved. So far, the mix of formal dispute panels and diplomatic pressure has ensured compliance without escalation to a trade war.

Successes and Failures Across Agreements, Reflecting on these agreements collectively

What Worked Well

- Gradual Liberalization with Compromise: Each agreement managed to chip away at barriers without collapsing the entire system. This gradualism prevented severe shocks. For example, USMCA’s modest 3.5% opening was politically palatable and economically absorbed with compensation. Over time, these small openings add up, showing success in moving towards freer trade incrementally.

- Enforcement and Dispute Resolution: The shift from NAFTA to USMCA markedly improved enforcement. The prompt resolution of the dairy TRQ dispute under USMCA is a success story in ensuring treaty obligations are meaningfully upheld. The WTO too was effective when engaged (e.g., the early 2000s dairy case ended an illegal subsidy). These successes build trust that agreements can be enforced.

- Avoiding Trade Wars: Despite fiery rhetoric at times, the U.S. and Canada have managed to avoid destructive trade wars over dairy. By embedding dairy issues into formal negotiations (NAFTA renegotiation, CPTPP talks) and legal forums, they resolved differences with rules rather than tit-for-tat retaliation. This is a success for rules-based trade.

- Economic Integration (to a degree): U.S. and Canadian dairy industries are slightly more integrated than before. Certain products flow more freely, benefiting both sides. For instance, U.S. producers of specialized ingredients found a stable market in Canada, while Canadian consumers gained from product diversity. Mexico’s full integration with the U.S. under NAFTA/USMCA is a model of success that highlights what could eventually happen if Canada further opened – U.S.-Mexico dairy trade flourished under free trade, supporting jobs and lowering prices.

- Maintaining Consumer Confidence and Standards: None of these agreements compromised food safety or quality standards – regulatory cooperation ensured that trade happens safely (e.g., mutual recognition of inspection systems). The success here is that increased trade did not lead to any health or safety scandals, preserving public support.

Where Did Disputes Arise / What Didn’t Work:

- TRQ Administration: A recurring failure has been the contentious administration of quotas. Canada’s tendency to allocate import licenses in protective ways led to disputes (USMCA, CPTPP panels). This suggests the agreements might have benefited from more precise rules upfront. The disputes themselves, while resolved, indicate this aspect “didn’t work” smoothly initially.

- Persistent High Tariffs: The fundamental high over-quota tariffs remain. No agreement succeeded in actually lowering those bound tariff rates significantly for dairy. Therefore, outside-quota trade is nil, and the distortion of extreme protection persists. The ultimate goal of free trade (tariff elimination) in dairy has not been achieved, reflecting a failure relative to textbook trade ideals.

- Limited Market Access: From the U.S. perspective, the dairy market openings achieved, while helpful, are still limited. U.S. negotiators failed to secure truly broad access. Canadian negotiators in turn failed (or chose not) to protect their system fully – each deal breached the previously sacrosanct supply management wall a bit more, which some view as a failure of political will to hold the line. This dynamic of mutual dissatisfaction – U.S. wanting more, Canada begrudging any concession – shows how none of the agreements delivered a win-win feeling on dairy.

- Ongoing Political Tension: Dairy remained a flashpoint in Canada-U.S. relations through these agreements, meaning the issue wasn’t fully put to rest. Even after USMCA, U.S. politicians complained of Canada’s “unwillingness to provide fair market access”. That such sentiments persist indicates a failure to attain a mutually satisfactory long-term solution.

- Domestic Adjustment Pains: While compensation helps, the need for it highlights failures in competitive adjustment. Canadian dairy still struggles with higher costs and cannot export effectively, meaning it hasn’t leveraged these agreements to become more competitive globally. The industry’s reliance on government payouts (billions of dollars for trade impacts) could be seen as a failure of the policy to adapt or innovate under pressure – essentially, money is spent to maintain the status quo rather than modernize.

- Trade Diversion: One subtle issue is that multiple overlapping agreements caused some trade diversion. For example, after CPTPP, New Zealand might fill some of Canada’s butter import needs that the U.S. might have otherwise supplied under WTO quota. Or EU cheese could preclude some U.S. cheese exports. The fragmentation of quotas by trade partner means the “success” for one partner is a “missed opportunity” for another. The U.S. being out of CPTPP meant it lost a chance for even more access; only bilateral negotiation (USMCA) got it back in. This is more a quirk than a failure, but it shows the complexity introduced by many layered agreements.

Lessons for Future: Trade Policy

Incrementalism vs. Big Bang: Attempts to radically overhaul dairy trade in one go would likely fail politically. Incremental opening, coupled with transition support, has proven feasible. Future policy should continue gradual liberalization, perhaps accelerating it slightly, but not shocking the system. Each small step (like a few extra percent of imports) can build towards long-run freer trade while giving industries time to adjust.

Importance of Domestic Reform: Trade agreements alone have limits if domestic policy remains rigid. One lesson is that domestic policy alignment is crucial. Canada’s experience suggests that proactively reforming supply management (to make it more market-responsive or cost-competitive) could ease external pressure and improve outcomes. Waiting to trade deals to force changes can put a country on the defensive. A future approach might involve Canada modernizing its dairy pricing or quota system domestically in tandem with offering market access – turning a concession into an opportunity for efficiency gains.

Detailed Rules Matter: The devil is in the details of quota administration and definitions. Future agreements should strive for clear, detailed provisions to prevent loopholes or ambiguity. For example, defining how TRQs should be allocated or ensuring new products are covered (so we don’t see another “ultra-filtered milk” gap) can save headaches. Transparency clauses, like those in USMCA, are valuable and should be standard to build trust that commitments are being met.

Enforcement and Dispute Settlement: Having a functional dispute mechanism is essential. NAFTA’s dairy carve-out was coupled with an inert enforcement regime – a lesson that lack of enforcement invites frustration and unilateral threats. With USMCA and CPTPP showing effective panels, future deals should preserve strong enforcement tools. Moreover, as seen, these tools should be used – early engagement via disputes can clarify rules and prevent issues from festering. Both sides should commit to working through established channels rather than resorting to rhetoric or punitive tariffs outside the agreements.

Acknowledge Sensitive Sectors Require Adjustment Aid: Another lesson is that to make trade liberalization politically viable, compensation and adjustment programs are not only helpful but perhaps necessary. Canada’s package for dairy farmers in exchange for trade openings set a model: essentially, buying out some of the quota rent loss. Future policy could formalize this approach – e.g., an agreement to gradually buy back quotas or fund diversification for farmers as market opens. The costs of compensation should be weighed against the long-term benefits of liberalization (like consumer gains and export opportunities). In essence, free trade in dairy may require upfront investment in those who lose out.

Avoiding Zero-Sum Framing: The history often framed dairy trade as Canada loses, U.S. wins (or vice versa). A lesson for future negotiations is to identify win-win aspects. For example, U.S. companies investing in Canada could create local jobs even as imports rise. Joint endeavors in dairy innovation or standards harmonization could accompany market access so both countries feel they are advancing together rather than one at the expense of the other.

Multilateral vs. Bilateral Solutions: The tangled web of bilateral quotas suggests that a multilateral approach (like a revived WTO effort) could theoretically be more efficient – one set of rules for all partners, avoiding trade diversion. However, the failure of Doha on agriculture teaches that broad consensus is hard. Thus, the lesson is that like-minded partners (e.g., the U.S. and Canada) might bilaterally or regionally agree on deeper integration in dairy outside the WTO framework. Perhaps a future North American dairy accord could allow more open trade but with common standards or even coordinated supply management across borders (a radical but interesting idea some economists have floated). In absence of that, working within smaller agreements like USMCA and CPTPP is the pragmatic path.

Consumer Interest Should Be Highlighted: Trade policy often centers on producers, but the lesson from high Canadian dairy prices is that consumers bear costs of protection. Future policy discussions might give more voice to consumer welfare – showing how a more open dairy market could lower prices, increase choice, and still maintain quality. Public support for reform could grow if consumers understand the stakes. Likewise, communicating to U.S. consumers that Canadian dairy (like specialty cheeses) could enrich U.S. markets if trade opened more might generate broader pro-trade constituencies.

Monitor and Adapt: Finally, a lesson is the value of ongoing monitoring and flexibility. The USMCA provision to revisit dairy after five years is wise – it acknowledges that conditions change (e.g., consumption trends, alternative dairy substitutes, etc.). Future agreements should include review clauses or sunset and renewal options for sensitive sectors, ensuring policies can adapt rather than be set in stone. If, for example, plant-based dairy alternatives significantly alter demand for milk, the whole context of dairy trade could shift – agreements must be able to adjust in response.

Conclusion

In conclusion, U.S.-Canada dairy trade has evolved from near stasis under CUSFTA/NAFTA to a slightly more open and rules-bound regime under USMCA, within a complex web of global and regional commitments. The road has been bumpy – marked by intense negotiations and disputes – but progress is evident. The key takeaway is that while trade agreements can open doors and set rules, they are most effective when accompanied by trust-building, transparency, and domestic readiness to change. Dairy remains one of the last bastions of protectionism in North American trade; the experience to date suggests that its future will be one of managed openness, not overnight free trade, guided by lessons learned over 30+ years of trial and error.

References

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2020, November 28). Government of Canada announces investments to support supply-managed dairy, poultry and egg farmers [News release]. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/agriculture-agri-food/news/2020/11/government-of-canada-announces-investments-to-support-supply-managed-dairy-poultry-and-egg-farmers.html

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2025). Canada’s dairy industry at a glance. Government of Canada. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/animal-industry/canadian-dairy-information-centre/dairy-industry

- Canadian Dairy Commission. (2022). Fact sheet: Supply management. Canadian Dairy Commission. http://www.cdc-ccl.ca/en/node/890