The Future of Global Dairy

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Self-Sufficiency Challenges

Market Outlook Through 2030: Supply, Demand and Price Projections

Sustainability Challenges and Strategies in Dairy

Regional Developments: Emerging vs. Developed Markets

Impacts of Macroeconomic Instability, Weather Extremes, and Geopolitics

Introduction

In December 2024, the 5th IFCN Dairy Forum gathered dairy economists and industry experts to assess the state of the global dairy market and its outlook. The analysis revealed an industry at a crossroads: milk prices have retreated from their 2022 peak but avoided the extreme lows of past downturns, while milk production growth in 2023 showed a modest recovery yet remained below historical trends. At the same time, structural challenges – from supply chain vulnerabilities and self-sufficiency gaps to sustainability pressures – are shaping decisions for market participants. This report synthesizes those findings, supplemented by recent data and research, to provide a comprehensive economic update. Key focal areas include recent price and production trends, supply chain resilience, forecasts through 2030, sustainability challenges, regional developments, and the impacts of macroeconomic, climatic, and geopolitical disruptions on dairy economics. The goal is to present a clear, data-driven overview of critical developments influencing global dairy markets, thereby informing decision-making for stakeholders.

Author’s Note

The analysis presented in this report is a synthesis of findings and perspectives shared during the 5th IFCN Dairy Forum 2024 and related sources. The author’s role is to summarize and contextualize these findings for informational purposes. The opinions, projections, and recommendations discussed herein reflect those of the original presenters and cited sources. They do not necessarily represent the views or endorsements of the author. Where appropriate, additional sources have been incorporated to support or clarify these findings.

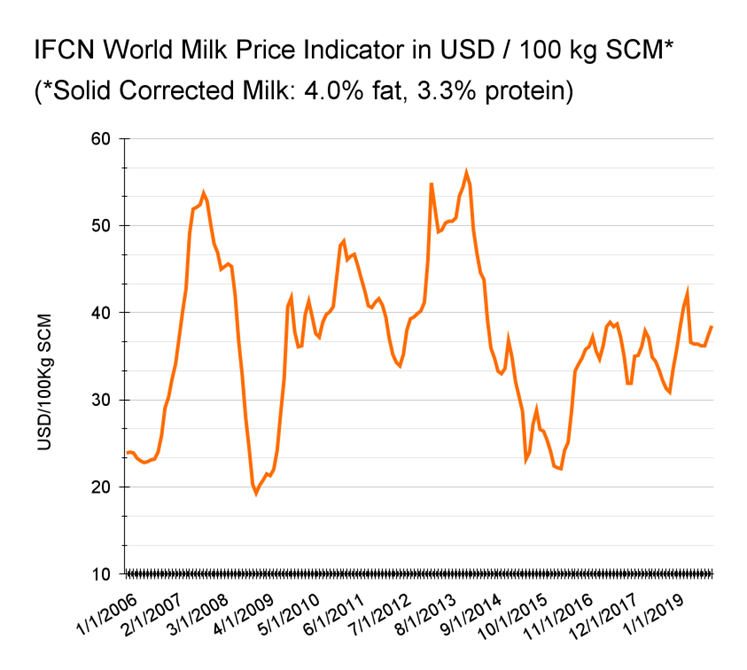

Milk Price Trends

Global dairy commodity prices have undergone a correction following the record highs of 2022. The IFCN World Milk Price Indicator fell by approximately 25% in 2023 compared to 2022, dropping to around 39–40 USD/100 kg (≈ 17.7–18.1 $/cwt) of standard milk (SCM). The trough occurred in Q3 2023 (about $36/100kg) (≈ 16.3$/cwt)– a notably higher floor than in previous price cycles (for instance, past downturns saw prices plummet to ~$19–22/100kg) (≈ 8.6–10.0 $/cwt). By late 2023 and into 2024, prices stabilized above $40/100kg (approximately 18.1$/cwt), considerably above the extreme lows of 2009 or 2016, reflecting a more muted “roller coaster” this cycle. Several factors prevented a deeper price collapse: a post-pandemic demand recovery (bolstered by rebounding food service and per-capita consumption growth) coincided with only a modest milk supply expansion. Indeed, even as prices eased, import demand from some key buyers began to revive, and many dairy importing countries worked down excess stocks, helping put a floor under world prices.

The IFCN Combined World Milk Price Indicator is based on the weighted average of 3 IFCN world milk price indicators: 1. SMP & butter (~32%), 2. Cheese & whey (~51%), 3. WMP (~17%), based on quarterly updated shares of the related commodities traded on the world market.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), international dairy prices weakened throughout 2023, and global milk trade volumes contracted for a second consecutive year. This price decline was driven by multiple demand-side factors: China sharply reduced its imports (especially of milk powders) as it drew on high domestic inventories, and demand in some regions was subdued by weaker purchasing power and slow recovery of food-service sectors. High dairy stock levels and increased local milk output in import-intensive regions (e.g. a surge of milk deliveries in Europe in early 2023) exerted additional downward pressure on world prices. By the final quarter of 2023, however, prices showed a modest rebound. Major export regions (Western Europe, North America, Oceania) faced tight export availability due to stagnating milk output, and at the same time some Western European markets saw unexpectedly strong domestic dairy demand – together these factors lifted global prices from their lows. Entering 2024, the IFCN milk price indicator stabilized in the low-$40’s/100 kg (approximately $18–$19 $/cwt), a level that balanced the still-weak overall import demand against the limited milk supply growth. Notably, this price level – while much lower than a year prior – was not sufficient to stimulate a robust supply response on its own. Producers worldwide remained cautious due to high input costs and other uncertainties (discussed below), preventing any flood of new milk that could once again depress prices. Looking forward, IFCN analysts expected a gradual firming of prices heading into 2025 as market fundamentals tighten slightly, though prices will likely remain below the previous peak. Overall, the recent price cycle underscores a new pattern: the global dairy market appears somewhat more resilient than in past downturns, with demand proving steadier and a higher cost floor supporting prices. This resiliency, however, comes with the flip side of persistent upward pressures if supply growth does not keep pace with demand in coming years.

Global Milk Production Trends

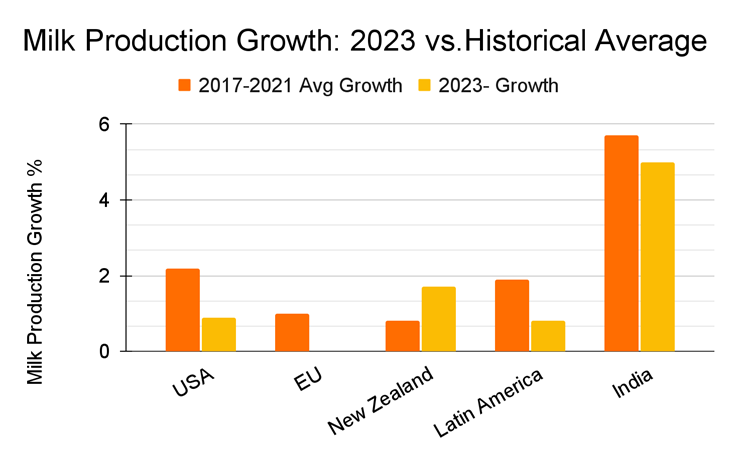

After an anemic performance in 2022, global milk production expanded at a quicker rate in 2023 – but the recovery was uneven across regions and still below the long-term average growth. World milk output in 2023 is estimated at about 965.7 million tonnes, up roughly 1.5% from 2022. This marked an acceleration from the mere ~0.6% growth seen in 2022, yet remains modest by historical standards (global milk production often grew ~2% annually in the past decade). The production gains were driven primarily by Asia, which now accounts for 45–46% of global milk output. India – the world’s largest milk producer – achieved around 5.0% growth in 2023, a slight slowdown from its ~5.7% average in recent years due to challenges like lumpy skin disease outbreaks and sporadic droughts. China’s milk production jumped by an even more impressive ~6–7%, spurred by supportive government policies and high farm-gate prices that incentivized expansion. These two countries alone contributed a large share of the global volume increase. By contrast, output gains in many traditional dairy-exporting regions were disappointingly small or nonexistent in 2023. In the United States, milk production edged up only 0.9% year-on-year – well below the U.S. historical average growth (~2%+). The European Union saw essentially zero growth (0.0%) in milk deliveries in 2023. European farmers faced high input costs (feed, energy, fertilizer) and increasingly stringent environmental regulations, which together capped output. In addition, several EU countries experienced drought in 2022 and a hot summer in 2023 that limited feed availability, curbing herd productivity. Other key producers had mixed results. New Zealand managed to increase milk volume by about +1.7% in 2023, rebounding from a poor prior season – a “base-year effect” aided by improved pasture conditions. Even so, Kiwi production remains vulnerable to weather volatility, and Kiwi farmers are grappling with high feed and fertilizer costs and new emissions regulations. Latin America’s aggregate milk output grew around 0.8%, below the region’s recent trend (~1.9% annual growth). Major South American dairy nations (e.g. Argentina, Brazil) were hampered by extreme weather swings – from droughts to heavy rains – and by economic challenges like input cost inflation and currency devaluations. In Africa and the Middle East, milk production growth generally remained sluggish (often under 1% per year), as structural issues such as poor infrastructure, feed shortages, and political instability persist in limiting dairy farm productivity. Overall, 2023’s fastest production growth was concentrated in a few emerging Asian markets, while most other regions underperformed.

From a supply perspective, the global milk supply in 2023 improved slightly but remained tight. The IFCN analysis noted that while 2023’s production growth was better than 2022’s near-zero growth, it was “still below the average,” contributing only marginally to easing the market. In many countries, farmers faced profitability pressures in 2023: lower milk prices coincided with still-elevated feed and energy costs for much of the year, squeezing margins. This dynamic discouraged aggressive expansion. Weather also played a significant role – for example, extreme heat and dryness in Europe reduced forage quality and yields in some regions, directly suppressing milk yields per cow, while floods in parts of Asia disrupted farm operations. On the whole, 2023 ended with a demand-supply balance that was tighter than initially anticipated when prices began falling. Milk production was essentially flat-to-down in several exporting regions at the same time as consumption was gradually firming. This tension set the stage for the stabilization (and nascent recovery) of prices described above. Easing feed costs and better weather in late 2024–2025 may enable a modest output uptick. On the other hand, structural constraints – labor shortages, environmental limits, and high financing costs – could keep growth moderate. The regional imbalances observed in 2023 (strong Asia vs. weak West) also carry implications: they signal that any future supply growth will likely be geographically uneven, with potential for persistent surpluses in some areas and deficits in others, complicating global trade flows.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Self-Sufficiency Challenges

A key theme of the IFCN Forum was the vulnerability of the global dairy supply chain due to heavy interdependence among countries. About 80% of countries are not self-sufficient in milk and thus rely on imports from surplus-producing nations. In other words, only a small group of countries/regions consistently produce more milk than they consume (notably the EU, New Zealand, the United States, Australia, and a few others), while the vast majority of nations run dairy deficits and depend on international trade to meet domestic demand. This structure creates inherent vulnerabilities. For deficit countries, any disruption in global supply – whether from trade policies, geopolitical conflict, or production shortfalls in exporter regions – can quickly translate into domestic shortages or price spikes. For surplus countries, demand shocks or import restrictions (such as sudden loss of a major export market) can lead to oversupply and farm price crashes. The dairy trade network is thus highly concentrated: for example, just five exporters (EU, New Zealand, US, Australia, and Argentina) account for the bulk of global milk powder and butter exports, and China plus a handful of other importers account for a huge share of import demand. This concentration means shocks are not easily buffered by diversification.

Recent events have exposed these vulnerabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war both disrupted logistics and input supplies, underscoring how geopolitical and supply chain crises can reverberate through dairy markets. In 2022, war-related spikes in feed, fertilizer, and fuel costs hit import-dependent regions especially hard, effectively taxing dairy-importing countries and sometimes prompting them to draw down reserves or seek new suppliers. Meanwhile, several traditional exporting regions have faced stagnating or declining self-sufficiency. Western Europe, for instance, has historically been a major surplus producer , but its surplus is projected to shrink somewhat by 2030 (to ~111% from 114% in 2023) due to environmental regulations and cost pressures on farmers. If Europe’s exportable surplus plateaus or declines, import-dependent regions must increasingly look elsewhere. However, other exporters have limits: New Zealand is near capacity due to land and environmental constraints, and the United States – while growing its surplus – faces internal policy debates and infrastructure bottlenecks in expanding exports. On the import side, many growing markets will not attain self-sufficiency despite investments. For example, China’s milk production is expanding but nowhere near enough to satisfy its fast-growing dairy consumption; by 2030 China is forecast to have an annual milk deficit on the order of 16–17 million tons (milk equivalent), a gap that will need to be filled by imports. This deficit alone is nearly as large as the entire milk surplus of the European Union. Similarly, regions like Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa are seeing demand growth outpace domestic milk output, implying continued or increased reliance on imported dairy products through 2030.

These self-sufficiency challenges raise strategic questions about supply chain resilience. Countries concerned about food security are exploring ways to reduce vulnerability – for instance, by diversifying import sources, investing in local dairy development (where feasible), and establishing safety nets (such as powder stockpiles or contract agreements) to buffer against global volatility. However, boosting domestic production in deficit regions often faces practical hurdles (climate, feed resources, cost of production, etc.), and in many cases achieving full self-sufficiency is not economically realistic. The more attainable goal is to build a resilient supply chain: that might include maintaining open trade relationships with multiple exporter nations, improving cold-chain and storage infrastructure to manage stocks, and enhancing local production efficiency incrementally. Surplus countries, on the other hand, are recognizing that their role as “dairy baskets” comes with responsibility and risk. Exporters benefit from access to growing markets but also must navigate trade disputes and diplomatic issues. For instance, recent tariff spats (such as China’s trade disputes with the EU in 2023) can indirectly threaten dairy trade flows. Any major exporter imposing export bans (as occasionally happens during domestic shortages) can send shockwaves through importing countries. Hence, the dairy supply chain’s interdependence means collective strategies are needed to improve stability – ranging from international policy coordination (to keep trade open even during crises) to joint investments in emerging dairy regions. At the forum, experts emphasized ensuring a “resilient dairy sector for the future”, which entails fortifying the supply chain against the types of shocks experienced in recent years.

Market Outlook Through 2030: Supply, Demand and Price Projections

Looking ahead, projections indicate that global dairy demand will continue to rise steadily through 2030, while supply growth may struggle to keep up under current constraints. The world population is expected to reach ~8.5 billion by 2030 (about +6.5% over 2023), and per-capita “milk equivalent” consumption is forecast to grow by ~5% (an increase of several kilograms per person). This implies total world demand for dairy products will expand roughly 1.5% per year on average – a continuation of the robust consumption growth observed in developing regions. Demand growth will be driven by income and population increases in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In many Asian countries, a rapidly growing middle class is incorporating more dairy into diets (e.g. greater cheese and fresh dairy consumption in China, Southeast Asia). Regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have large untapped potential for higher dairy intake if incomes rise and supply becomes more accessible. Notably, Asia’s per capita dairy consumption is projected to climb strongly by 2030, yet many Asian countries will still consume far less per person than Western countries, leaving considerable room for further demand expansion beyond 2030. On the supply side, the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook (2023–2032) baseline projects world milk production to increase about 1.5% per year over the next decade, reaching roughly 1,030 million tonnes by 2032. This rate is similar to demand growth in percentage terms. However, the sources of production growth are heavily skewed: over half of the global milk output increase is expected to come from just two countries – India and Pakistan – which have rapidly expanding dairy sectors and will account for nearly one-third of world milk output by 2032. In contrast, milk production in some developed regions is forecast to stagnate or even decline. The EU, for example, is projected to produce slightly less milk by 2030 as it transitions toward stricter environmental standards and faces quota-free market pressures. Similarly, other traditional exporters like New Zealand are unlikely to see significant volume growth due to environmental and land limits. The United States may achieve moderate production increases through continued efficiency gains, and could play a larger role in export markets if its surplus grows (US self-sufficiency is forecast to rise to ~112% by 2030).

Crucially, production growth in many low-consumption developing countries will lag behind demand growth. As noted, large import-dependent regions are not forecast to close the gap with consumption by 2030. For instance, Southeast Asia and Africa will likely see their net dairy imports rise, because even though local milk output will grow, it won’t match the rapid increase in demand. The OECD-FAO outlook projects a slowdown in global agricultural trade growth to ~1.3% annually in the coming decade, largely because middle-income countries will account for a greater share of consumption and tend to have slower import growth as their domestic industries develop. Even so, net import requirements for dairy are set to remain substantial and even expand in absolute terms for regions like East Asia and the Middle East. The balance between supply and demand by 2030 could be precarious. If the optimistic end of production forecasts (1.5% growth/year) is realized, it may roughly meet the projected demand increase – but any shortfall in supply growth would cause demand to outstrip supply. The IFCN long-term analysis warns of a potential “milk shortage” scenario by 2030 if current trends persist: by their estimates, global milk demand could exceed attainable supply by on the order of 10 million tons (milk equivalent), meaning that volume would either go unmet or require drawing down stocks. Such an imbalance would put upward pressure on prices. In economic terms, the price outlook toward 2030 is firm – the combination of growing demand, higher production costs (due to sustainability measures and inflation), and slower supply growth in key export regions is expected to support higher average real prices for dairy commodities. This does not preclude cyclical fluctuations (weather or economic shocks will still cause short-term volatility), but the floor of the market may rise. Indeed, consumers in import-dependent, low-income countries are at risk of reduced access to dairy if prices climb faster than incomes. Affordability could become a concern, highlighting the importance of productivity improvements to keep dairy products accessible.

In summary, the medium-term outlook suggests a need for significant investment in dairy productivity and supply expansion to keep pace with demand growth sustainably. If environmental and cost constraints prevent the needed supply growth, the world could enter a period of structurally tight dairy markets by the late 2020s, characterized by frequent regional shortages and high prices. Stakeholders are therefore closely watching indicators like global herd size, yield improvements (through genetics or feeding), and policy developments that affect production incentives. Encouragingly, some regions (South Asia, the Americas) still have potential to grow output if given the right support, which could alleviate the pressure. Nonetheless, market participants should prepare for a scenario of persistent tightness, in which strategic planning (such as forward-contracting imports, managing price risk, and investing in local production where possible) will be key.

Sustainability Challenges and Strategies in Dairy

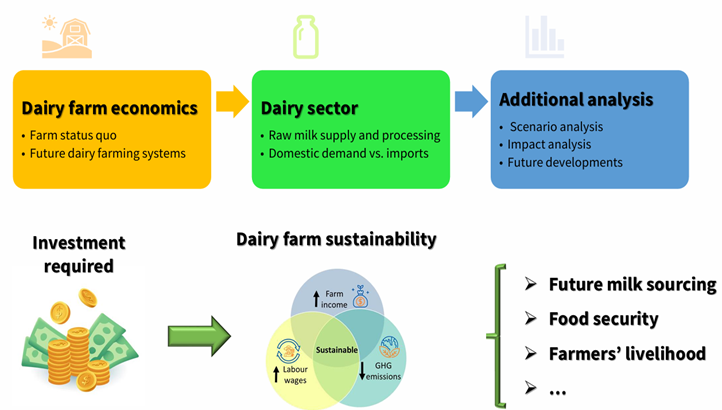

Sustainability—environmental, economic, and social—has become a central talking point when discussing the dairy industry’s future. The global dairy sector is under intensifying pressure to reduce its environmental footprint while maintaining profitability and meeting rising demand.

Discussions and recent research highlight several sustainability challenges with economic implications:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Dairy cows and their manure emit methane and nitrous oxide, greenhouse gases. There is growing regulatory and consumer pressure for the dairy industry to cut emissions. The EU’s climate policies and New Zealand’s pioneering methane reduction targets are examples of measures that could impose additional costs or production limits on dairy farms. Farmers may need to invest in solutions like feed additives (to reduce enteric methane), manure management systems, or carbon offsets – all of which affect cost structures. Regions that move faster on emissions regulation (e.g. Europe) could see output growth slow and production costs rise, at least in the short term. Conversely, failure to address emissions might risk long-run viability if carbon pricing is implemented. Many dairy companies are also setting net-zero emissions goals in their supply chains, effectively passing sustainability requirements down to farms.

- Water and Land Use: Dairy production is resource-intensive, often straining water supplies and land availability. In water-scarce areas, dairy farms face scrutiny for groundwater use and effluent management. Regulations (such as limits on groundwater extraction or manure spreading in Europe’s nitrate-vulnerable zones) can constrain expansion or require new investments (e.g. in waste treatment). Land use pressure, including deforestation concerns with feed production, is prompting moves toward more sustainable feed sourcing and even limits on herd expansion in sensitive areas. These trends may cap growth in certain regions and necessitate efficiency gains (higher yield per cow) to decouple production from resource use. Efficiency improvements – like better genetics, precision feeding, and optimizing herd health – are thus both economic and environmental imperatives.

- Economic & Social Sustainability of Farms: A less-discussed but critical aspect of sustainability is the economic survival of dairy farmers. High input costs, volatile milk prices, and stringent regulations can make dairy farming financially unsustainable, leading to farmer exits. This is especially acute in regions like Europe where smaller family farms struggle to afford compliance with environmental rules and in developing countries where farmers lack capital for modern equipment. The forum touched on securing dairy income in the context of social sustainability, stating that without viable farm economics, other sustainability goals are hard to meet. Strategies here include risk management tools to handle price swings, cooperative models to give farmers market power, and government support during transitions (for example, grants for installing methane digesters or for pasture improvement).

- Consumer Perceptions and Demand Shifts: Sustainability is also influencing consumer behavior. There is a rise in plant-based dairy alternatives and calls for “climate-friendly” diets. If the dairy sector is perceived as environmentally harmful, it risks losing market share or facing demand-side constraints. Thus, investing in sustainability is partly a strategy to maintain consumer trust and demand. Many dairy companies now market sustainability credentials (grass-fed, carbon-neutral milk, etc.) to appeal to conscious consumers. While this can be a competitive advantage, it requires verification and sometimes costly changes in practice.

Addressing these challenges requires a combination of innovation, regulation, and collaboration. As one recent study noted, there is an “urgent need for innovation, regulatory action, and meeting consumer demand for more sustainable practices” in dairy. Innovation includes developing cost-effective technologies: for example, feed additives that cut methane without sacrificing productivity, climate-resilient forages, automation to improve efficiency, and perhaps breeding lower-emission cattle. Many of these innovations can improve environmental outcomes and farm profitability simultaneously (the so-called win-win scenarios), but they need scaling up and investment. On the regulatory side, smart policy design is crucial – regulations should set clear sustainability targets but also provide flexibility and support so farmers can adapt without undue financial strain. For instance, incentive-based approaches (like payments for ecosystem services or carbon credits for dairy farms) could encourage sustainability while offsetting costs.

Industry stakeholders are also pursuing collaborative strategies. The forum highlighted the importance of cooperation between farmers, processors, retailers, and governments in building a sustainable dairy future. Examples include processor-funded programs to help farmers reduce emissions, public-private partnerships to develop manure-to-energy projects, and knowledge-sharing networks (such as IFCN itself) to spread best practices globally. International initiatives (like the Global Dairy Platform’s sustainability goals) aim to align efforts and avoid duplication. Ultimately, the economic dimension of sustainability boils down to improving resource efficiency – producing more milk with less environmental impact per unit. This tends to reduce costs in the long run (through improved productivity) even if it requires upfront investment. Many developing regions have large efficiency gaps (for instance, milk yields per cow in Africa or South Asia are a fraction of those in Western Europe), so targeted investment there could boost supply and sustainability simultaneously. In sum, the dairy sector’s sustainability journey presents challenges – regulatory compliance costs, need for R&D, potential short-term supply constraints – but also offers opportunities for innovation-led growth. Those producers and companies that proactively adapt are likely to be more competitive and resilient in the 2030 horizon, whereas regions slow to adopt sustainable practices may face either trade barriers or environmental crises that undermine their dairy industries.

Regional Developments: Emerging vs. Developed Markets

Developed Dairy Exporters

In the traditional dairy heartlands of North America, Europe, and Oceania, recent developments reflect adaptation to both market and policy forces. The European Union remains the world’s largest dairy exporter by volume, but as noted, its milk production has plateaued. Environmental regulations (climate targets, manure management rules, limits on herd expansion to control nitrogen) are increasingly binding, particularly in countries like the Netherlands, Ireland, and Germany. Coupled with high energy and feed prices in 2022–2023, this has created a challenging environment for EU dairy farmers, squeezing margins and dampening growth incentives. Nonetheless, the EU industry is focusing on higher-value products – e.g., specialty cheeses, infant formula – to drive export earnings even if volumes stagnate. The EU’s global market influence is also evident in price transmission: increased EU milk deliveries in early 2023 helped push down world prices, whereas any future shortfall in EU output would tighten world supply. Going forward, Western Europe is expected to see only minimal output changes; the OECD outlook even foresees a slight decline in EU milk output by 2030. This means Europe’s role as a surplus supplier might slowly diminish, with implications for importers that rely on EU exports.

In the United States, the dairy sector is in a phase of expansion and structural change. U.S. milk production hit record levels in 2021–2022, then slowed in 2023 due to herd contraction. The U.S. has a large, technologically advanced farm base and abundant feed resources, suggesting it could ramp up production if market signals turn favorable. The IFCN forum pointed out “technological advancements” as a key driver that could raise U.S. self-sufficiency from 105% to 112% by 2030, implying more milk available for export. Indeed, the U.S. is strategically aiming to increase its share of global dairy trade (through export initiatives by organizations like USDEC). Challenges include trade uncertainties (tariffs, trade agreements), and environmental/regulatory issues at the state level (e.g., California’s methane law). The U.S. also faces internal market volatility – high feed costs and interest rates in 2023 hurt smaller farms and accelerated consolidation. Still, with modest demand growth domestically, any production growth above that will feed into exports. The U.S. could become a more dominant butter and cheese exporter by late in the decade, provided it addresses logistic and policy hurdles.

Oceania (New Zealand and Australia) has traditionally punched above its weight in dairy exports, especially for milk powders. New Zealand in particular exports ~95% of its milk output. Lately NZ dairy farmers have been confronting a confluence of difficulties: high input costs, new environmental regulations (including a coming pricing mechanism for agricultural emissions), and more frequent adverse weather (the past season saw cyclone damage and an El Niño pattern reducing pasture growth). Fonterra, NZ’s largest processor, has tempered its production forecasts, and the national herd has been slowly shrinking from its peak. As a result, NZ’s milk output is unlikely to grow substantially in the near future; any gains will come from productivity rather than herd expansion. For 2024, NZ milk production was forecast to be flat to slightly down despite improved payout prices, due to these structural issues. Australia has seen a longer-term decline in milk production (down ~20% from a decade ago) amid farm exits and droughts, making it a less significant exporter than before. These trends in Oceania mean that the global market cannot count on growth from this region; at best, Oceania will maintain its current export volumes, and any global demand growth will need to be met by others.

Latin America is a region with potential to become more of a dairy exporter, but performance is mixed. Countries like Argentina and Uruguay produce a surplus in most years and export milk powders and cheese (primarily to Algeria, Brazil, and Russia markets). However, Latin America’s overall self-sufficiency is just below 100% (about 94–96%), meaning as a whole the region is nearly balanced between production and consumption. Brazil, the largest producer, oscillates between slight surplus and deficit and mostly supplies its own huge domestic market. In 2023, high grain prices and drought in the south constrained Brazilian milk output, turning Brazil into a net importer temporarily. The outlook shows Latin America inching toward self-sufficiency by 2030 (rising to ~96% from 94%), thanks to investments in yield improvements and herd expansion in countries like Argentina, Peru, and Chile. If political and economic stability improve, South American producers could increase exports, but frequent macroeconomic instability (inflation, currency volatility) remains a hurdle. For example, Argentina’s dairy farmers struggled with inflation over 100% in 2023, making planning and investment difficult. Additionally, climate variability (from Amazon influences in Colombia to Pampas droughts) makes Latin American milk output erratic year to year. Thus, while the region may contribute marginally more to global supply by 2030, it is not poised to be a game-changing exporter on par with the EU or US.

Emerging Markets and Developing Regions

On the demand side, Asia will continue to be the engine of growth in global dairy consumption. We have discussed China and India – China’s import needs remain enormous, and India’s growth, while prodigious in volume, is largely internally consumed. Beyond these two, other South Asian countries (Pakistan, Bangladesh) and Southeast Asian nations (Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines) are seeing rapid demand growth. Many of these countries have programs to boost local milk production (for instance, Vietnam has been investing in large-scale dairy farms, and Pakistan is working on breed improvements), yet structural limitations mean domestic output meets only a fraction of demand. Indonesia and the Philippines, for example, rely on imports for over 80% of their dairy needs. The forum included perspectives from countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Malaysia, indicating that developing countries face common challenges: inadequate cold-chain and processing infrastructure, limited access to finance for farmers, feed supply issues, and competition from cheap imports which can discourage nascent local industries. In Africa, consumption is rising due to population growth and urbanization, but production often lags. For instance, Nigeria has a large demand for dairy but imports the majority of its milk powder due to an underdeveloped local dairy sector (hindered by nomadic production systems and lack of investment). Ethiopia has one of Africa’s bigger milking herds but struggles with low yield per cow and market access for smallholders. These constraints mean African and many Asian countries will remain import-dependent in the medium term, as reflected in self-sufficiency projections.

One notable trend is regional integration: some emerging markets are trying to source more from regional neighbors to reduce reliance on distant suppliers. For example, China is investing in dairy production in Belt-and-Road partner countries; Middle Eastern importers are partnering with Eastern European and Central Asian producers. Such developments could slightly reconfigure trade flows (with new origins like Belarus, Turkey, or India playing a growing role in certain export markets). Still, the overarching reality is that a handful of exporting countries will serve the needs of a widening base of importers. As emerging markets grow, they are also diversifying the product mix – demand for butter and cheese is rising alongside milk powders, which will require importing countries to develop cold chains and importing firms to adapt (cheese and butter are more perishable than powder). This could spur investment in local processing capacity in some places (e.g., recombining milk powders into liquid milk locally, or packaging imported cheese in consumer-ready form).

In summary, developed markets are focusing on efficiency and value addition amid plateauing milk volumes, whereas developing markets are trying to ramp up production but will largely rely on imports to satisfy booming demand. Regional developments thus underscore a core theme: the global dairy map is evolving gradually, but no radical shifts in who produces or who consumes are expected by 2030. Instead, incremental changes – a bit less surplus here, a bit more demand there – will cumulatively stress the system. Market participants in each region must navigate their unique situation: EU farmers managing new environmental rules, U.S. exporters building supply chains abroad, Oceania staying competitive under climate policies, and emerging market governments balancing trade vs. local farm development. Those strategic choices will collectively shape the global dairy equilibrium.

Impacts of Macroeconomic Instability, Weather Extremes, and Geopolitics

The dairy economy does not exist in a vacuum – it is highly sensitive to broader macroeconomic, climatic, and geopolitical events. The period 2020–2024 vividly demonstrated how external shocks can ripple through dairy markets, affecting both supply and demand:

- Macroeconomic Instability: High inflation and economic slowdowns in many countries have direct effects on dairy. When inflation surges and real incomes fall, consumers (especially in developing countries) often cut back on non-essential or higher-value dairy products. The 2022–2023 global inflation spike, partly driven by supply chain disruptions and war, eroded dairy demand in price-sensitive markets (e.g., less purchasing of imported milk powder in parts of Africa and the Middle East). Concurrently, dairy farmers faced soaring input costs – feed, fuel, fertilizer, energy – which squeezed profit margins and, in some cases, forced farmers to cull cows or exit dairying (thus tightening supply). The combination of weaker demand growth and constrained supply growth can lead to inconsistent outcomes: initially, as seen in 2023, demand softness dominated and prices fell; later, supply contraction loomed and prices stabilized. High interest rates (a response to inflation) are another factor – they increase financing costs for farm operations and dairy processing expansion projects, potentially stalling investment in needed capacity. Emerging economies with debt and currency issues (such as Argentina or Pakistan) saw their dairy sectors particularly strained by the macro environment. The importance of stable macroeconomic conditions for dairy was highlighted: stability seems to fosters consumer confidence (steady dairy consumption) and enables farmers to invest in expansion. By contrast, instability appears to forces short-term coping measures that can have long-term output consequences.

- Weather and Climate Events: Dairy farming is inherently dependent on climate and weather patterns. Extreme weather events in recent years have had drastic impacts on feed availability, animal health, and milk output. For example, the European summer drought of 2022 severely reduced pasture growth and silage yields, leading to a drop in milk production in late 2022 and early 2023 in affected countries. Likewise, flooding in Pakistan and India disrupted local dairy supply chains and caused animal losses. The forum noted that extreme weather conditions directly affect milk and feed production – a trend expected to worsen with climate change. The 2023 occurrence of back-to-back hurricanes in New Zealand’s North Island not only hurt milk production but also spiked insurance costs for farmers. Meanwhile, heat stress on cows during recurring heatwaves (in Europe, North America, and Australia) has measurably lowered milk yields during summer months. All these events contribute to greater volatility in milk supply. Weather-induced supply shocks can lead to sudden price rallies (as seen when New Zealand’s production dips or when drought hits an exporting region). They also raise costs – feed must be imported or bought at high prices when local forage fails, as South American producers experienced during recent droughts. The growing frequency of such extremes has made climate resilience a priority: farmers are adopting mitigation measures (shade, cooling systems, drought-tolerant forages), and companies are incorporating climate risk into sourcing strategies. Nonetheless, the industry is coming to grips with the reality that year-to-year milk output variability may increase, which complicates market planning and amplifies the need for buffer stocks and flexible supply chains.

- Geopolitical Events: Geopolitics play a significant role in dairy trade and input markets. The clearest example is the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which erupted in early 2022 and had widespread repercussions. Ukraine and Russia are major suppliers of grains and oilseeds; the war disrupted these exports and sent global feed prices to record highs, inflating feed costs for dairy farmers worldwide. It also spurred fuel and fertilizer price spikes (Russia being a key fertilizer exporter), further straining farm economics. Additionally, the conflict led to the loss of Ukraine’s dairy exports and shifts in trade flows (e.g. some countries had to source butter from alternate suppliers). Another geopolitical factor is trade policy and sanctions. Ongoing sanctions on Belarus (a notable milk powder and butter exporter) have re-routed some trade. Import policies in large markets like China can turn on political considerations – e.g., China’s retaliatory tariffs on Australian dairy (imposed in 2020 amid a diplomatic row) caused Australia to divert exports elsewhere. The forum also cited new tensions like the EU-China spat over unrelated tariffs (electric vehicles) that nonetheless “highlight growing sensitivities in China’s trade relations” and could indirectly affect agri-food trade sentiment. Geopolitical conflicts and tensions often impact supply chains, feed availability, and energy prices, creating a cascade of effects on dairy. Moreover, policy responses to global events – such as export restrictions – can be disruptive. In 2022, some countries briefly considered banning dairy exports to protect domestic consumers (as was seen for other foods like wheat in various nations). While widespread dairy export bans did not materialize, the mere possibility adds uncertainty.

Overall, the past few years have reinforced that dairy markets are global and interconnected, vulnerable to shocks from far outside the barnyard. For market participants, this underscores the importance of building resilience. Strategies being adopted include: diversifying sourcing of inputs (e.g., feed), using risk management tools (like commodity futures or options to hedge price swings), holding strategic reserves of dairy products, and improving transparency and communication along the supply chain to respond quickly to disruptions. International cooperation is also crucial – for instance, keeping trade routes open and not resorting to protectionism during crises benefits overall stability. From a policy perspective, some governments are re-evaluating the balance between food self-sufficiency and globalization in light of recent shocks. For dairy, this might mean more support for local production in importing countries (to buffer against import hiccups) as well as collaborative efforts among exporters to ensure reliable supply. In an economic sense, instability and shocks introduce additional costs and risks that must be managed: they can cause input cost surges, demand slumps, or sudden windfall gains, all of which complicate investment and production decisions. The dairy industry is learning to adapt to this higher-risk environment. For example, dairy processors are expanding multi-origin supply chains (sourcing milk powder from more than one country) and farmers are adopting financial tools to cope with input cost volatility. The expectation is that climate and geopolitical risks will remain elevated, so resilience and flexibility will be key themes in dairy economics moving forward.

Conclusion

The global dairy market as of 2024 stands at an inflection point. The immediate pressures of the recent boom-bust price cycle have subsided into a tentative equilibrium of stable prices and modest supply growth. However, beneath this calm lie transformative forces. Demand for dairy is steadily climbing, driven by population and income growth in emerging markets, while supply faces headwinds from high costs, environmental constraints, and recurring disruptions. The analysis from the IFCN Dairy Forum 2024 and supporting data suggests the coming years could see structural tightness in dairy markets – firming prices and periodic shortages in import-dependent regions. To navigate this, they suggest dairy industry stakeholders consider efficiency, innovation, and risk management. Investments in productivity (better genetics, feeding, technology) may help produce more with less and reconcile sustainability goals with output growth. Building resilient supply chains – through diversification, strategic partnerships, and perhaps maintaining inventories – will help cushion against macroeconomic and climatic shocks. Policy-makers have a role in creating an enabling environment, whether through supporting research, providing safety nets, or facilitating fair trade. Sustainability efforts, while challenging, can be turned into opportunities for value addition and differentiation if managed wisely.

The dairy sector is challenged to simultaneously ensure it can profitably supply world demand and do so in an environmentally and socially sustainable manner. The economic signals are clear: efficiency and resilience will be rewarded in an era of tighter margins and greater volatility. Strategic decision-making – informed by data and trends such as those discussed in this report – will be critical. The IFCN Forum’s dialogue underlined that securing a “resilient dairy sector for the future” is not just a slogan but a pragmatic necessity. As we approach 2030, the global dairy market’s trajectory will depend on how well the industry adapts to the changes underway. Continued monitoring of key indicators (milk production growth, consumption patterns, price movements, and sustainability metrics) will be vital. This 2024 market update provides a foundation for understanding the current state and challenges; the task ahead is to translate this understanding into strategies that ensure the dairy sector’s profitability in the years to come.

References

- Bhat, R., & Infascelli, F. (2025). The path to sustainable dairy industry: Addressing challenges and embracing opportunities. Sustainability, 17(9), 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093766

- Dairy Farmers of Canada. (2024). Recovery in global dairy prices despite market uncertainty. Quarterly Skim – Fall 2024, 3–4. https://dairyfarmersofcanada.ca/en/dairy-in-canada/market-intelligence

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2024). Dairy market review – Emerging trends and outlook in 2023. FAO. Summary retrieved from The DairyNews. (2024, May 1). Global milk production surged to 965.7 million tonnes in 2023. https://thedairynews.com/en/global-milk-production-surged-to-965-7-million-tonnes-in-2023/

- IFCN. (2024, December 4). Navigating milk shortages and shaping a sustainable future for global dairy demand [Conference presentation]. 5th IFCN Dairy Forum. International Farm Comparison Network. https://ifcndairy.org

- IFCN. (2024). IFCN Dairy Report 2024. International Farm Comparison Network. https://ifcndairy.org/ifcn-products-services/dairy-report/

- OECD, & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2023). OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2023–2032. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/19428846-en

Milk, Cookies, and Christmas Eve: Santa’s Dairy Tab by the Numbers

Milk, Cookies, and Christmas Eve: Santa’s Dairy Tab by the Numbers Dairy Market Dynamics and Domestic Constraints: A Dairy Sector Assessment as of June 2025

Dairy Market Dynamics and Domestic Constraints: A Dairy Sector Assessment as of June 2025 U.S.–Canada Dairy Trade Relationship (2025–Present)

U.S.–Canada Dairy Trade Relationship (2025–Present) Suspension of FDA’s Grade “A” Milk Proficiency Testing Program – A Comprehensive Analysis

Suspension of FDA’s Grade “A” Milk Proficiency Testing Program – A Comprehensive Analysis