Grain markets have been noted in history as early as during the Roman Empire. Though scholars used the term “market” more in the abstract sense, considering the basic economic forces of the ancient economy, such as supply and demand, production and productivity, market integration, and the relationship of both the peasant farmer and the wealthy aristocrat to the grain market.

A bread stall, from a Pompeiian wall painting, Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011)

1208: English Grain Markets

Grain marketing was next noted by researchers as early as 1208, when the English grain market was both extensive and efficient. The market was extensive in that transport and transactions costs were low enough that grain flowed freely throughout the English economy from areas of plenty to those of scarcity. The grain market was efficient in the sense that profit opportunities seemed to have been largely exhausted. During the 1200s, grain was stored efficiently within the year. Large amounts of grain were also stored between years in response to low prices in order to exploit profit opportunities from anticipated price increases. There is indeed little evidence of any institutional evolution in the grain market between 1208 and the Industrial Revolution some 500 years later.

1862 to 1916: U.S. Homestead Acts

Now we skip ahead to the United States grain market. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American agriculture expanded geographically and developed technologically. A series of Homestead Acts in 1862 to 1916 granted settlers ownership of Western farmland. A land-grant complex of education, research, and extension was established to increase agricultural knowledge and keep farmers and farm families abreast of new farm and home technology.

Photograph 69-N-13606C; Family with Their Covered Wagon During the Great Western Migration 4

1917: Food Control Act

Supplying wheat to Europe and other allies during and immediately after World War I launched American agriculture onto the international scene. Claiming “wheat will win the war,” the Food Control Act of 1917 encouraged wheat production with a fixed market price for farmers.

1929: Agricultural Marketing Act

However, reliance on U.S. grain exports created an unstable post-war market once European production recovered. The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 barely stabilized farm prices, demonstrating that effective supply management required production controls.

1933: Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 marked the beginning of federal supply management of agricultural products and represents America’s first comprehensive farm bill.

1938: “The New Deal”

The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, also known as the New Deal, addressed environmental degradation that began during the previous era of agricultural expansion. The Soil Conservation Service, known today as the Natural Resources Conservation Service, became a permanent USDA agency during this time.

1940s & 1950’s: Productivity Increases

World War II led to an era of expansive production for American farmers. By 1942, surpluses were depleted and some soil conservation programs were put on the wayside as farmers took advantage of higher prices. Productivity increases from this era accelerated through the 20th century as technologies like commercial seed, petroleum-based inputs, and mechanization were widely adopted. By the early 1950s, farmers faced similar market conditions as after World War I. European production increased, American surpluses grew, and the whole US economy risked recession. While U.S Congress passed the Smith-Lever Act in 1914 which created a system of Cooperative Extension Services, a 1955 amendment to the Smith-Lever Act charged extension services to help unproductive farmers.

First WI Extension agent, E.L. Luther made his rounds on a two-cylinder motorcycle.

1970s: “Russian Grain Robbery” and plant “Fencerow to Fencerow”

International geopolitics and transitions in domestic policy precipitated another tumultuous era of agricultural production in America. In 1972, the United States arranged to export to the Soviet Union a quantity of wheat that exceeded 80% of America’s domestic wheat demand. Dubbed the “Russian grain robbery,” this policy challenged domestic demand, tripled wheat prices, doubled corn and soybean prices, and increased several livestock prices in the United States by mid-1973. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz implored American farmers to plant “fencerow to fencerow” to increase the supply of agricultural commodities and to capture perceived economies of scale necessary to combat high production costs. The combination of production oriented policies and improvements in agricultural technology created almost immediate surpluses in commodity crops, especially corn. The Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 replaced the New Deal era concept of parity with target payments and deficiency payments to support farmers’ incomes as prices were allowed to fall.

1980s: Farm Crisis

The 1980s Farm Crisis developed into the worst financial situation in agriculture since the 1930s. Unfortunately, the Agriculture and Food Act of 1981 was enacted before the emerging crisis was fully understood. A bumper crop in 1982 set record surpluses and government crop inventories reached new highs. Depressed commodity prices and farm incomes, record carryover crop inventories, and a worsening global economic situation shaped US farm policy in the mid-1980s.

1996: “Freedom to Farm”

The 1996 farm bill brought major reform to commodity programs. The main outcome of the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 is underscored by its popular name: “Freedom to Farm.” This policy increased flexibility by removing acreage restrictions from commodity production; it also decoupled income support payments from crop prices and replaced deficiency payments with direct compensatory payments.

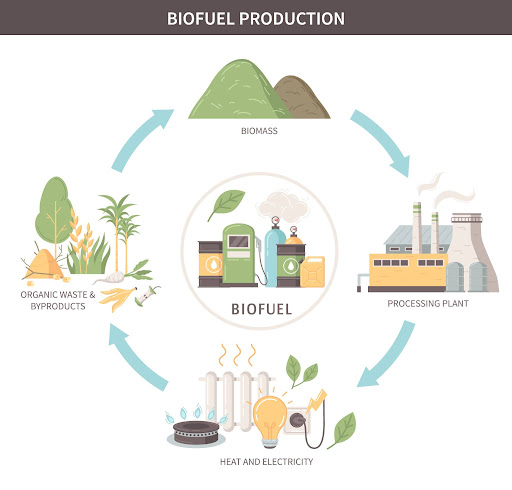

2000s: Biofuels

Slight changes in subsequent farm bills have impacted grain markets. For example, the biofuel industry brought American agriculture into new market territory. The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 became the first farm bill to explicitly include an energy title. Farm bill energy programs focused primarily on development of the biofuel industry through research, grants, and loans, while separate energy bills in 2005 and 2007 expanded mandates for biofuel use.

Image by macrovector on Freepik

Summary

In summary, many aspects have impacted and shaped the grain market as we know it today. The flow of grain through the marketing channels from the farmer to the end user has been continually changing over time. Increased grain supplies and changing demand for grain and grain products have been largely responsible for altering the grain marketing system.

The changes which grain marketing has undergone over the years has resulted from several factors:

- larger farm production units,

- technological advances in harvesting grains,

- changes in marketing channels to increase efficiency,

- improved transportation methods,

- government programs, and

- changing demands of grain end users.

A lot of unknowns exist which is why farmers should increase their knowledge of grain marketing. Successful grain marketing requires diligence, knowledge, patience, perseverance, and flexibility.

References:

- Paul Erdkamp. 2005. The grain market in the Roman Empire : a social, political and economic study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, viii, 364 pages : maps ; 24 cm. ISBN 0521838789

- Gregory Clark. 2015. “Markets before economic growth: the grain market of medieval England.” Cliometrica, Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History, Association Française de Cliométrie (AFC), vol. 9(3), pages 265-287, september.

- D. McGranahan, et all. 2013. “A historical primer on the US farm bill: Supply management and conservation policy.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 68 (3) 67A-73A; DOI: https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.68.3.67A.

- Photograph 69-N-13606C; Family with Their Covered Wagon During the Great Western Migration; 1866; WPA Information Division Photographic Index, ca. 1936 – ca. 1942; Records of the Work Projects Administration, Record Group 69; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/family-covered-wagon, December 20, 2023]

This material was developed by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Division of Extension in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Wisconsin counties. This material is based upon work supported by USDA/NIFA under Award Number 2021-70027-34694.

A Brief History of Crop Insurance

A Brief History of Crop Insurance Identifying Factors of a Grain Marketing Plan

Identifying Factors of a Grain Marketing Plan Defining a Grain Marketing Plan

Defining a Grain Marketing Plan Evaluating a Farmer’s Risk Tolerance

Evaluating a Farmer’s Risk Tolerance